VAQAR, The new generation of fashion avant-garde

Vaqar is a cool Iranian fashion label based in Tehran that has participated in the prestigious LVMH Prize For Young Fashion Designers in 2016.

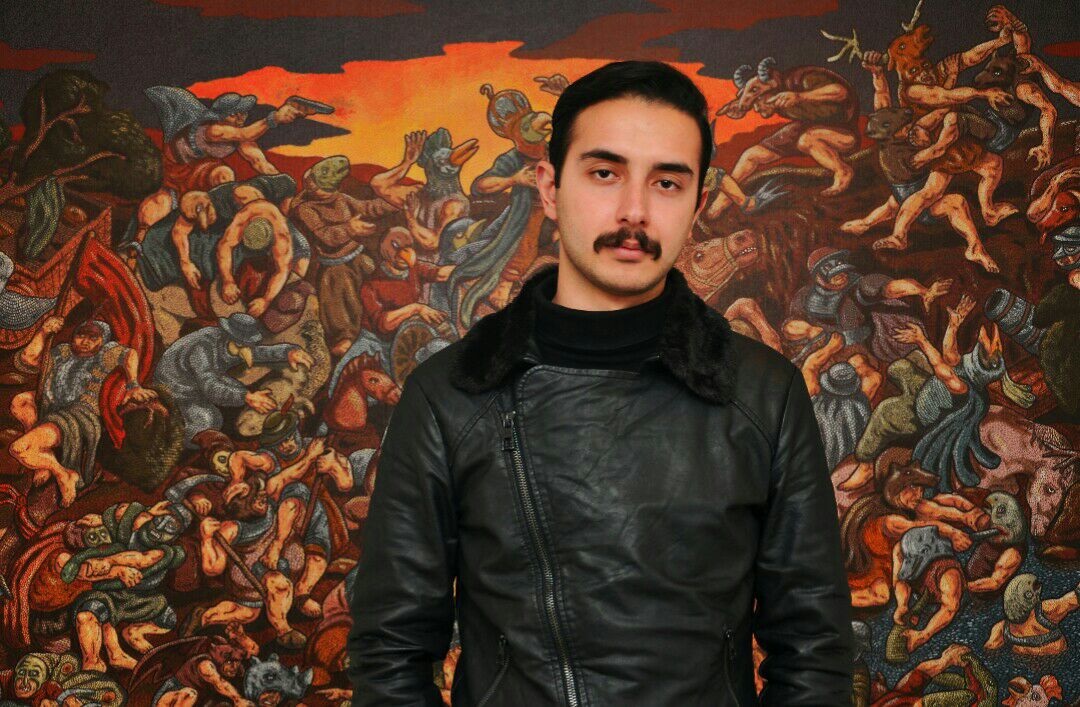

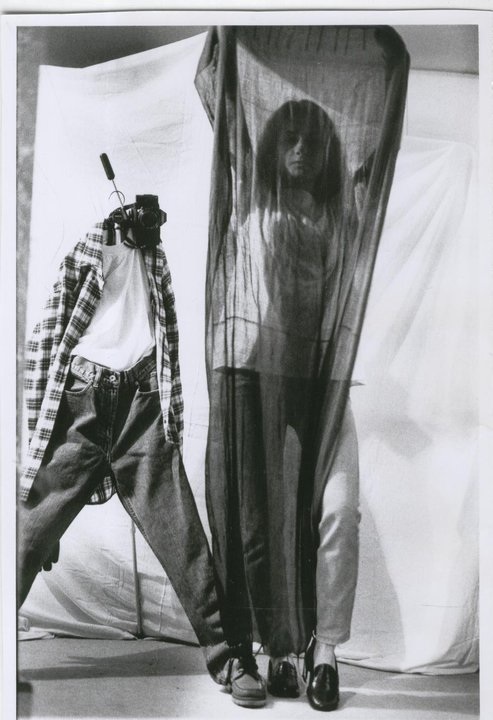

Behind this young label there are two beautiful and creative sisters, Shiva and Shirin Vaqar, designing fashion in a contemporary style with an universal appeal and bringing a fresh wind and a redefined concept of modernity into the international fashion scene.

They will show their Spring/Summer 2018 collection during Paris Fashion Week in September.

In 2016 you’ve been invited to participate at the LVMH Prize For Young Fashion Designers. How was this experience? Was it the first time that you were presenting your fashion brand outside of Iran?

It was an amazing experience like a turning point for us and it encouraged us to push ourselves harder. It was our first time we presented our work outside of Iran.

Despite the fact that there is neither a fashion school in Iran nor an institution that supports young Iranian fashion designers, how come you’ve decided to work in fashion? What did you study initially and when did you launch your label “Vaqar”?

I studied Business Management and Shirin studied Visual Arts. We’ve always had this desire to work together and fashion was something that we were both very curious about. So we decided to give it a try and started Vaqar in 2013.

Tell me more about the fashion scene in Iran. Do you observe a progress in the support and promotion of Iranian fashion labels?

Recently fashion is getting more serious in Iran and there is more support. The biggest support comes from the Iranian people who have started to give more attention to Iranian brands. That’s why there are also more fashion events which is a big motivation for us designers.

“We think it is just the beginning of Iranian fashion and in a few years it will get even better.”

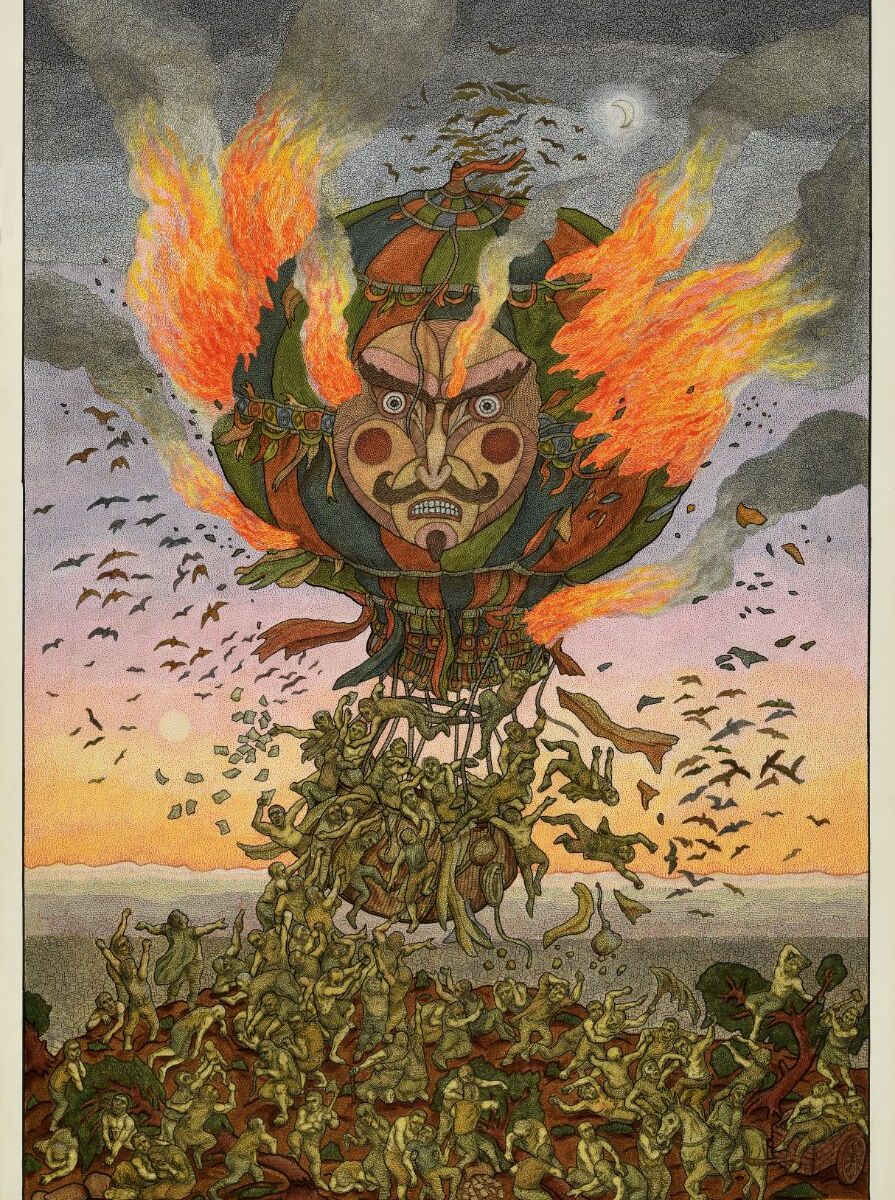

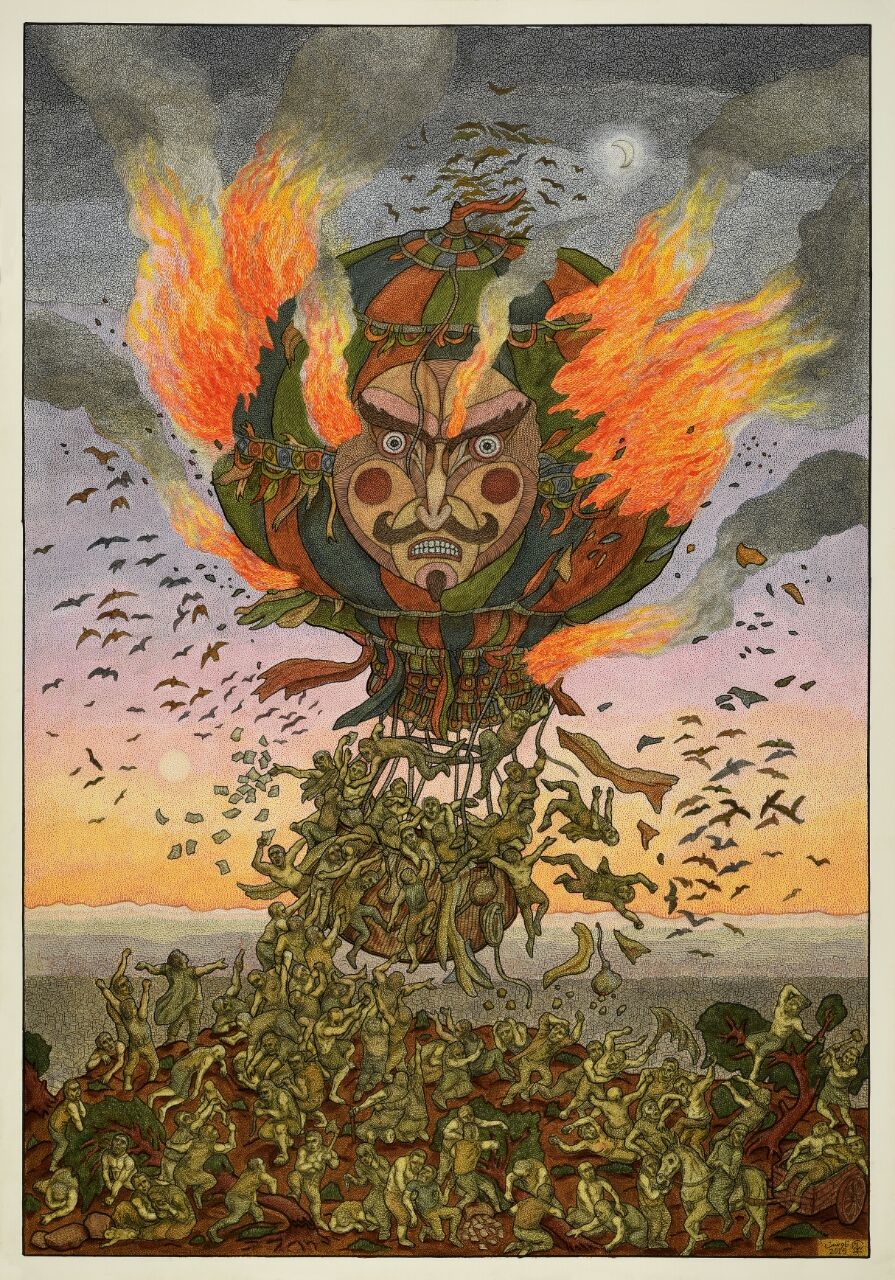

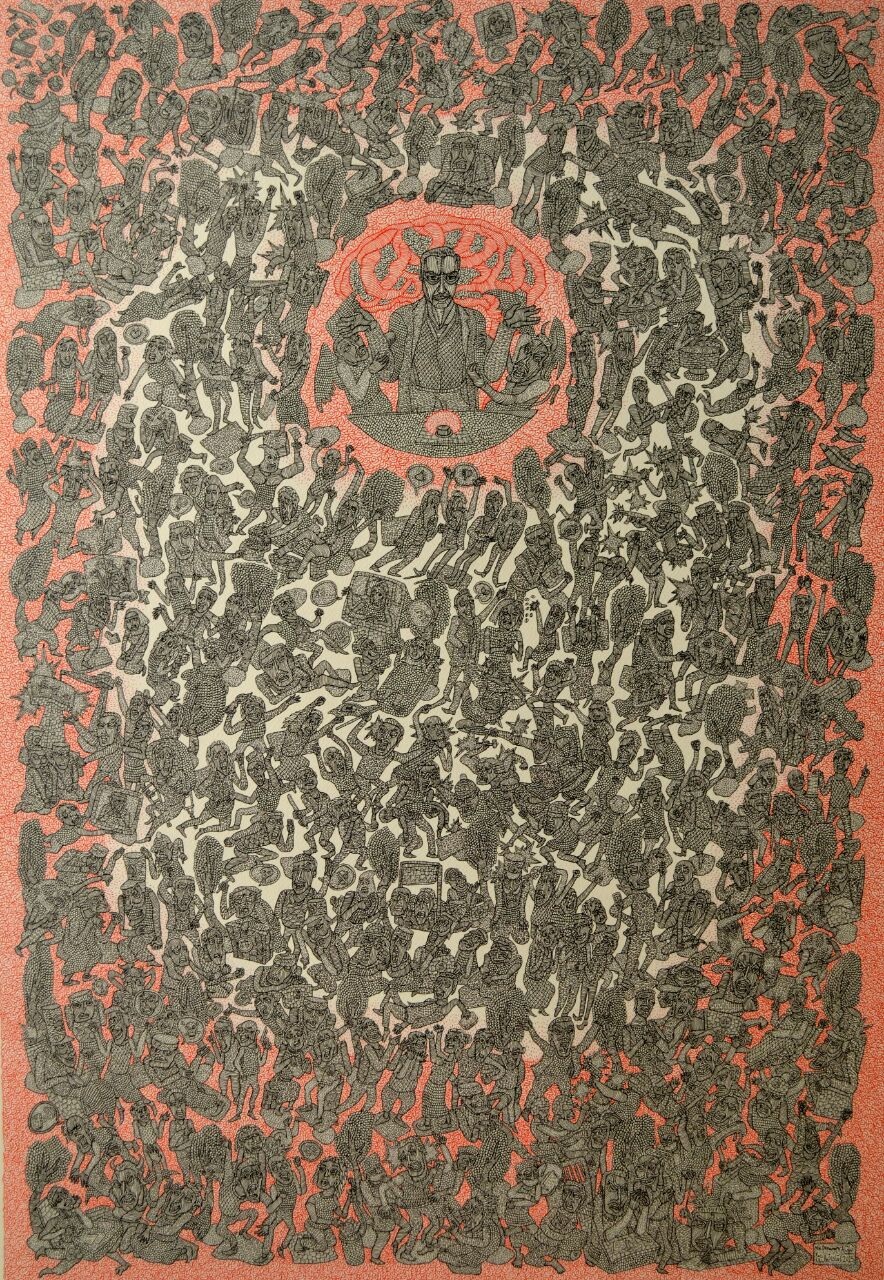

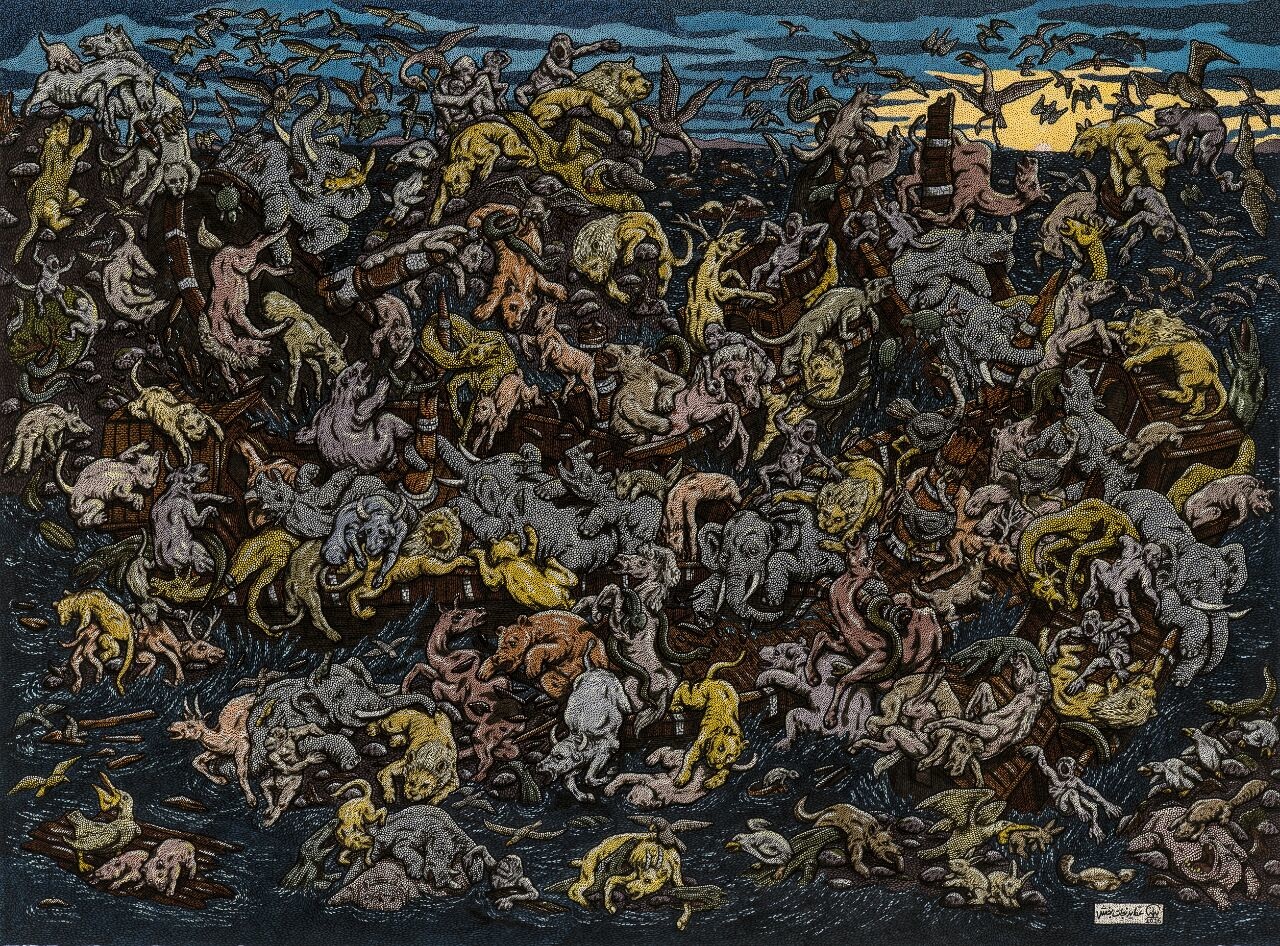

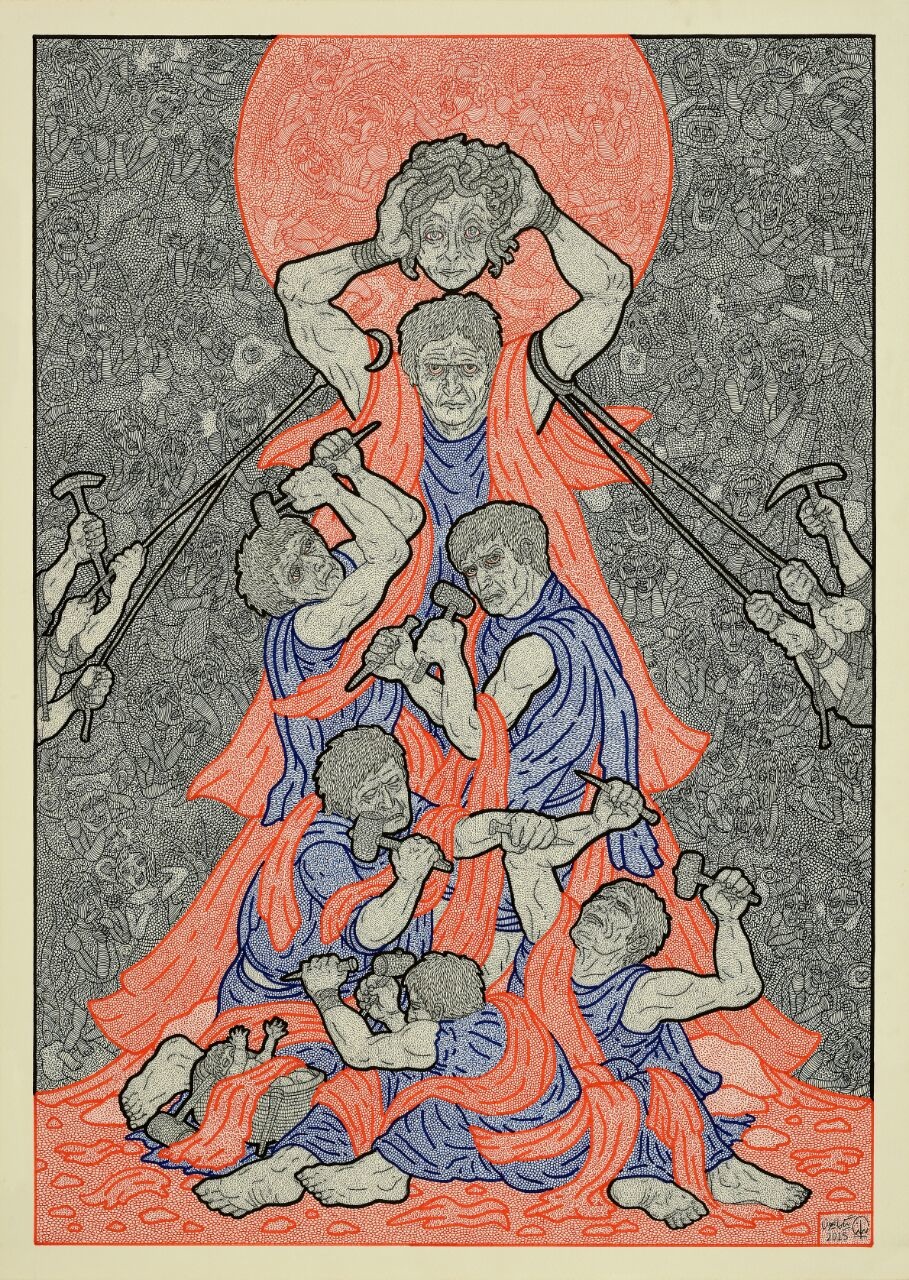

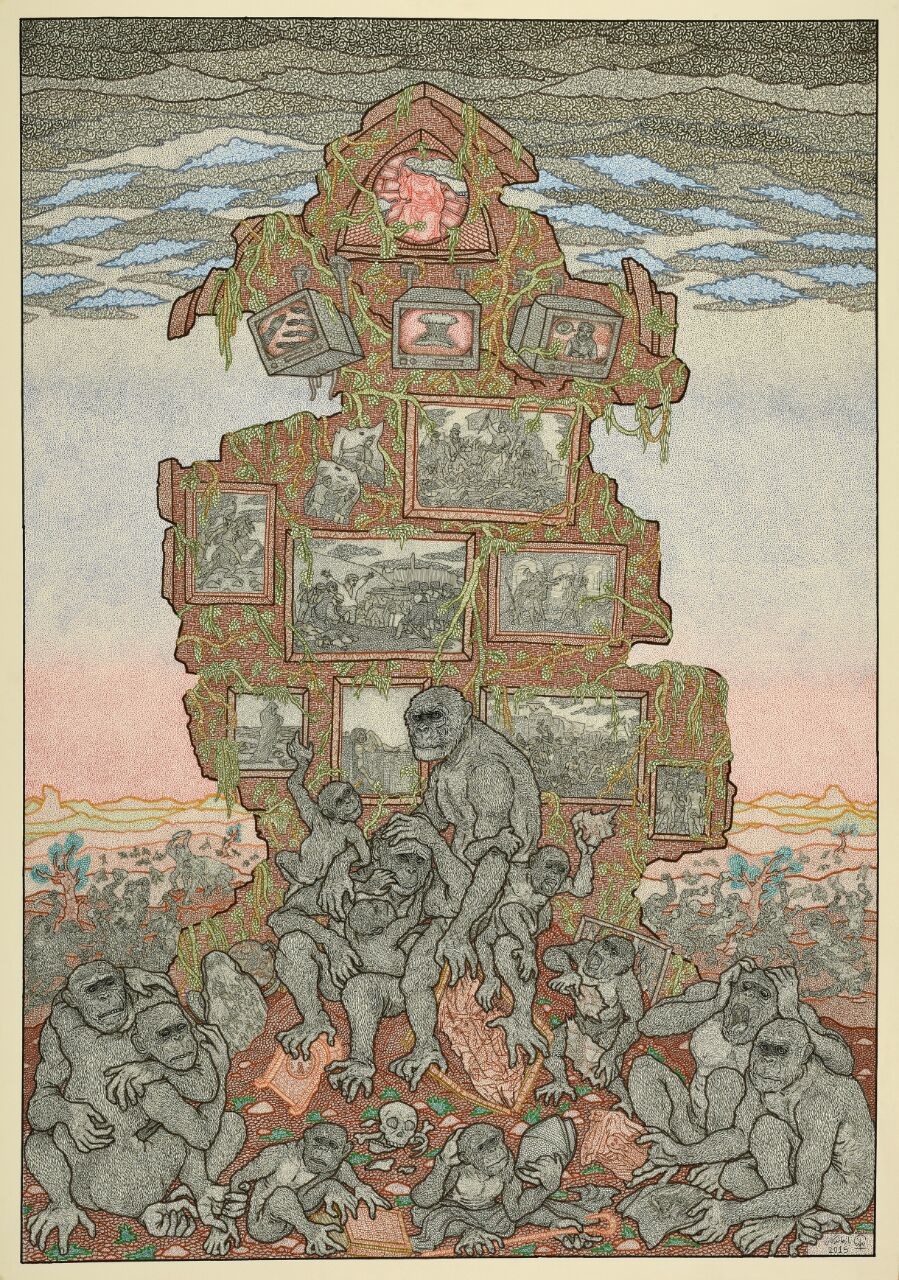

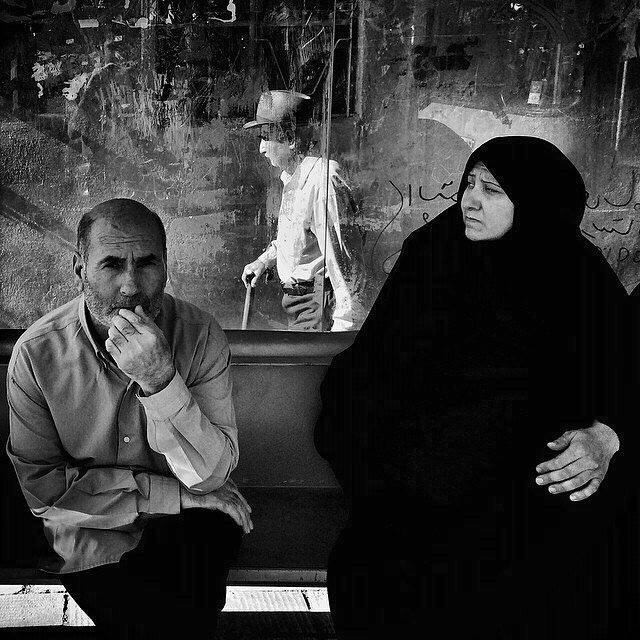

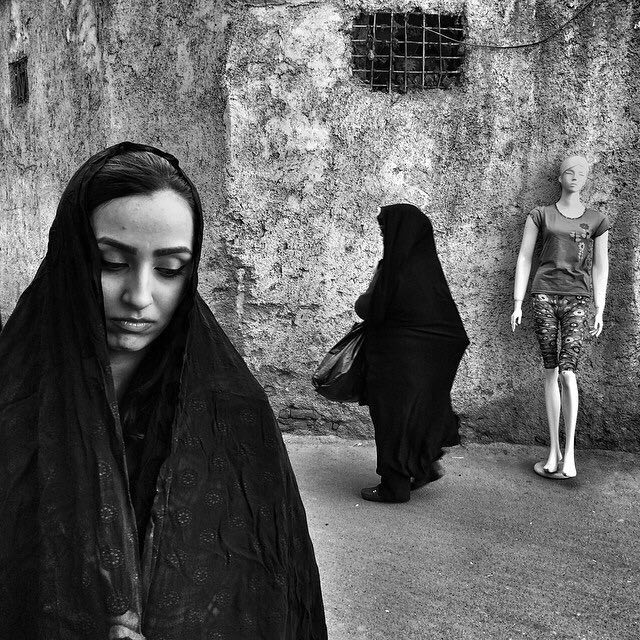

Your style is very contemporary with a universal appeal. What inspires you? Is Iranian culture a source of inspiration for you?

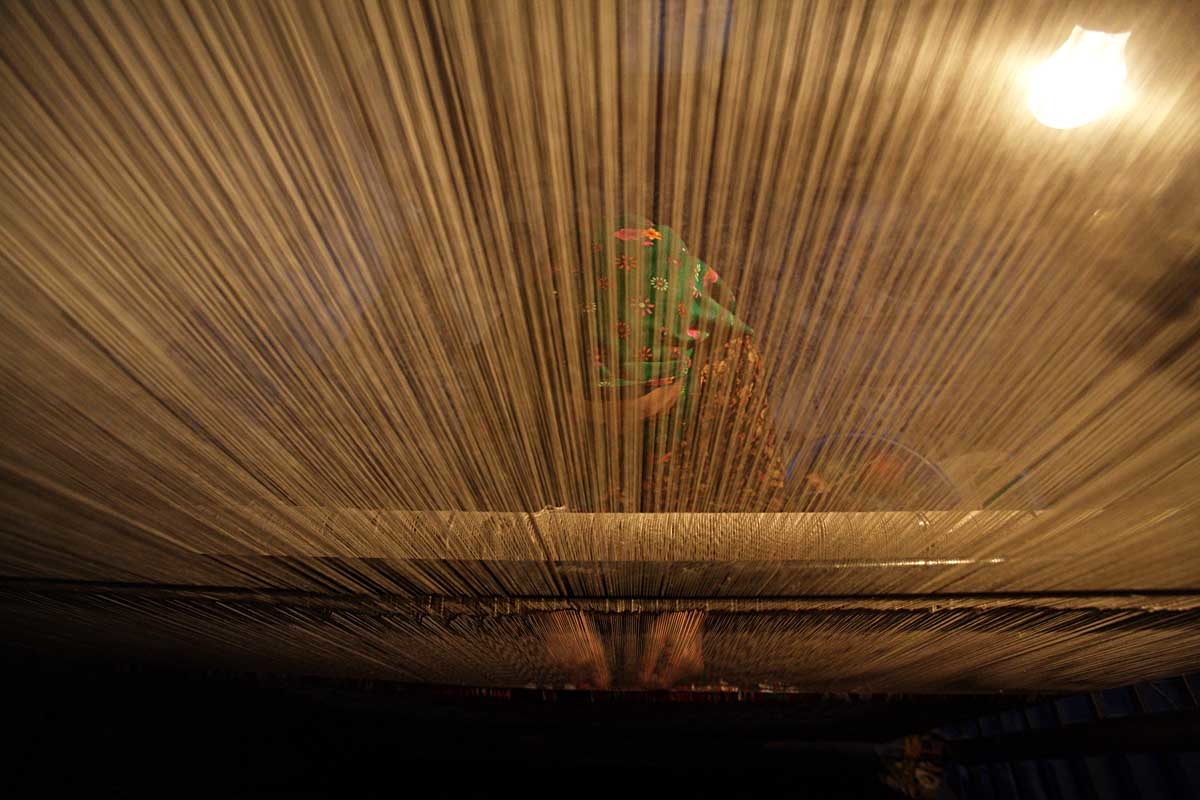

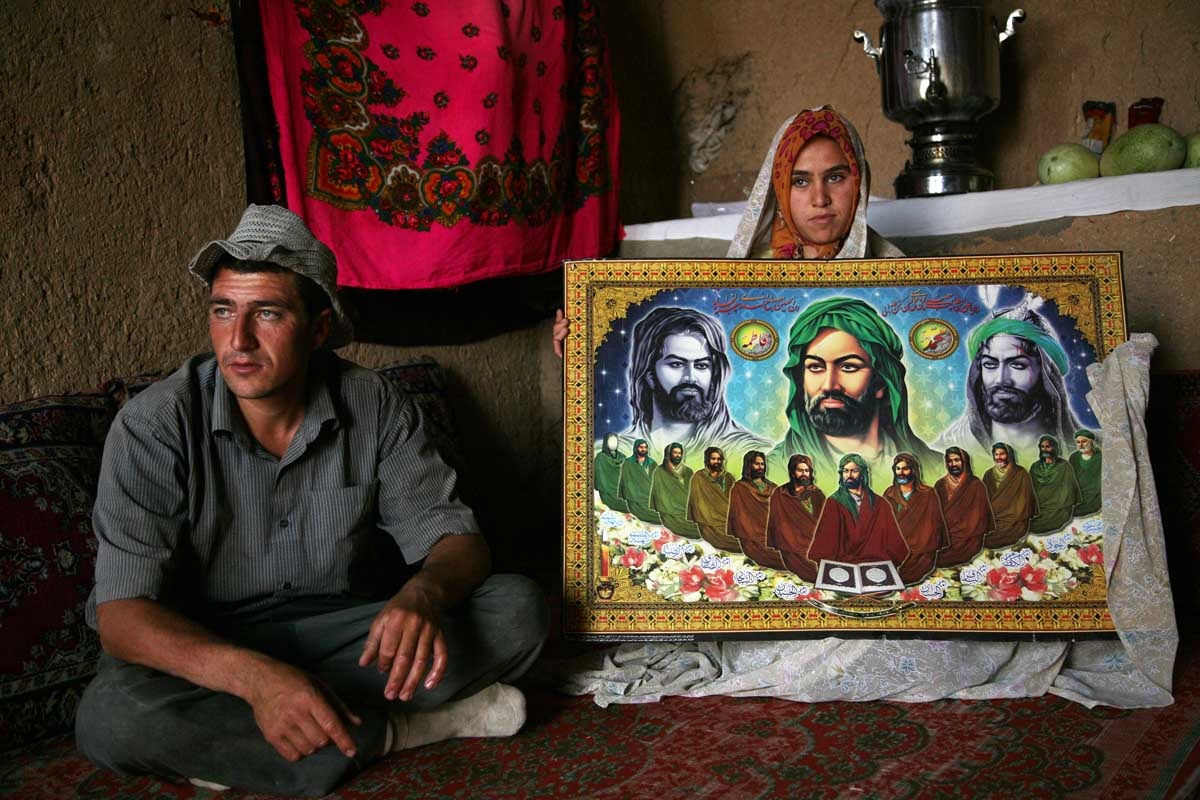

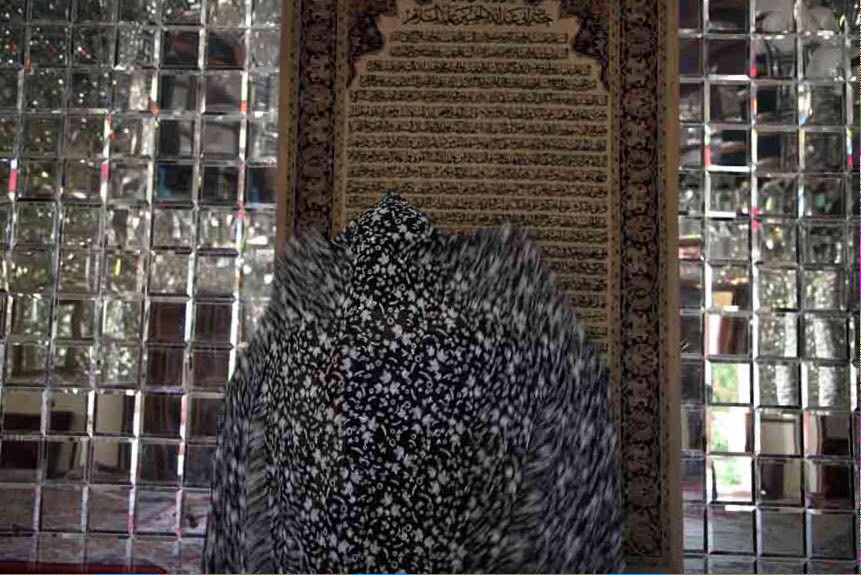

We get inspiration from almost everything. We always try to modernize the outdated styles with a new and fresh approach based on our inspirations.

“The impact of our cultural heritage on our clothes is undeniable.”

The values that are the conclusion of our culture can have an impact on our mindset and eventually on our clothes.

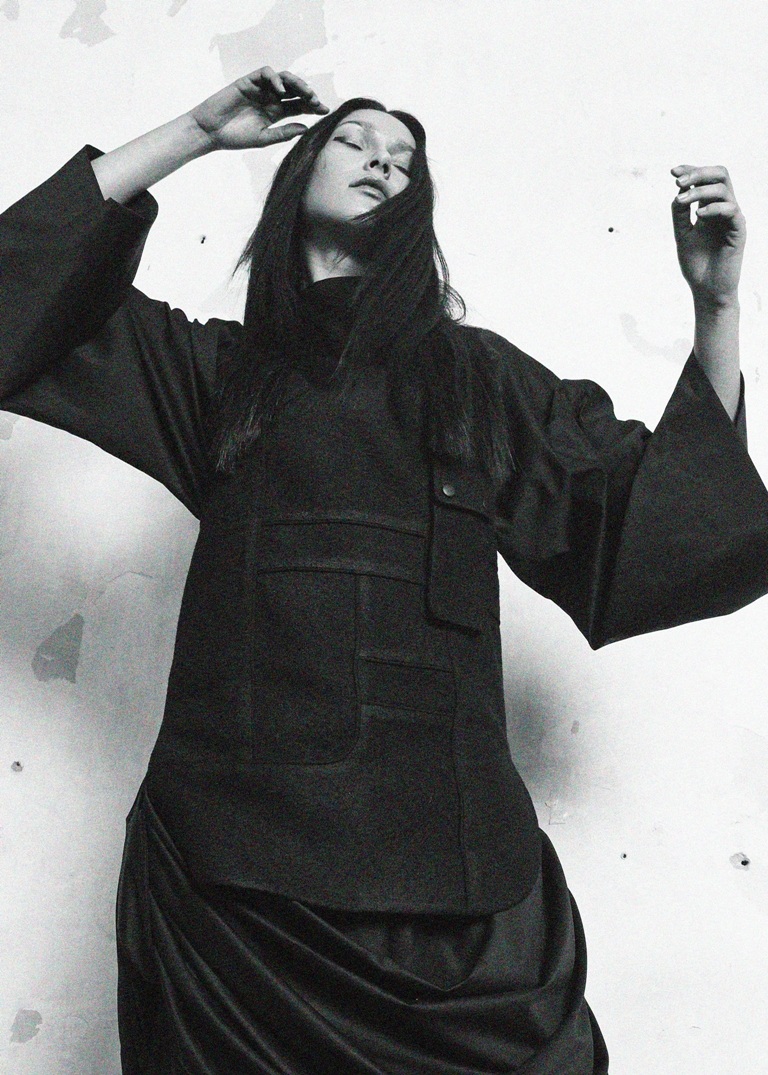

Your modern and very constructive style in monochromatic colors reminds me of fashion icons such as Yohji Yamamoto or Rei Kawakubo. Have these designers influenced your creative evolution?

We love Yohji Yamamoto. However the colors we use are totally based on the concepts we choose and the concepts we choose are the result of our mood in a certain period of time. So we don’t feel any obligation in our work to use just monochromatic colors.

Being sisters, what is the advantage or disadvantage of working together?

We haven’t felt any disadvantage at all, on the contrary. As we know each other very well, it’s easier for us to understand each others’ points of view and to get to a final idea or decision. Our different skills can complete each other and make them more efficient.

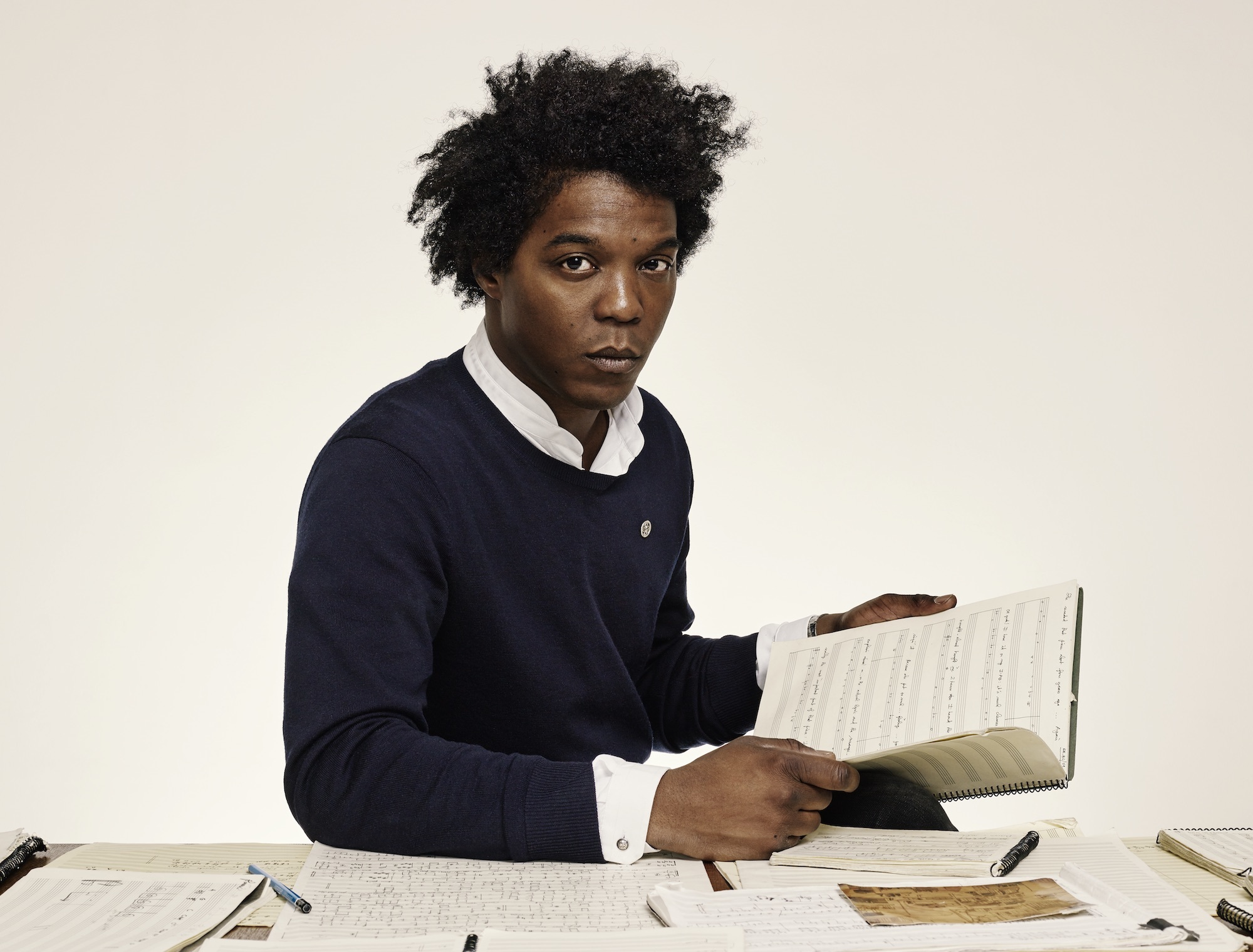

Do you work with music? What are you listening to right now while working on your next collection?

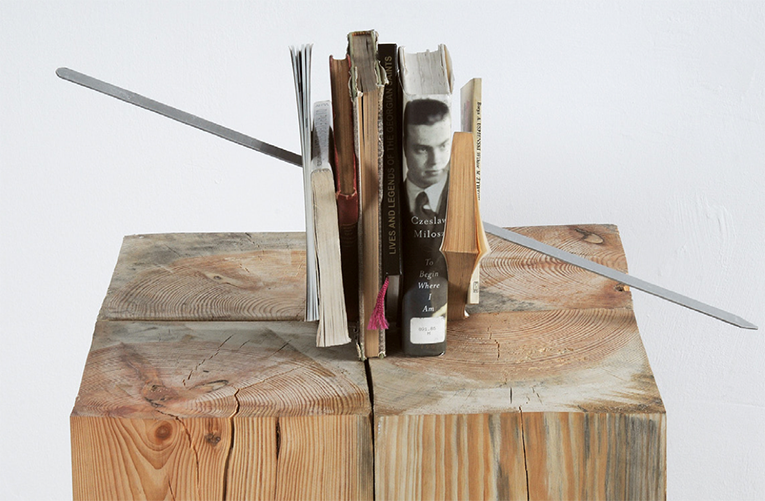

Music is a big part in our design progress. Recently we’re listening to Olafur Arnalds tracks, especially Til Enda and Gleypa okkur.

When and where will you show your next collection? Could you give me a little idea about the look of your Spring/Summer 2018 collection?

We usually present a collection at the beginning of each season in Tehran and twice a year at Paris Fashion Week.

This year we will probably show our Spring/Summer 2018 collection during Paris Fashion Week end of September.

“The look of the next collection will be a modern version of traditional garments with an affection for Iranian ancient statues.”

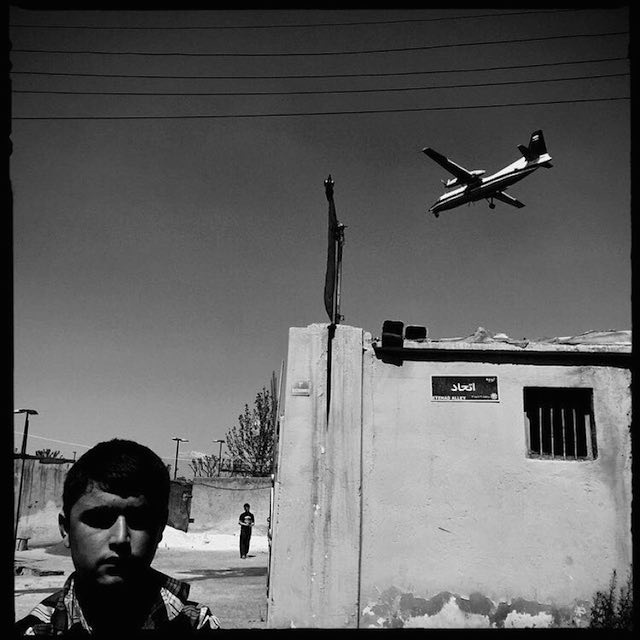

You’re living in Tehran, what do you like about this city? What are your favorite spots?

The thing we like about Tehran is its nostalgia.

Our favorite spots are places like Tehran Bazaar, Tajrish…

Credits:

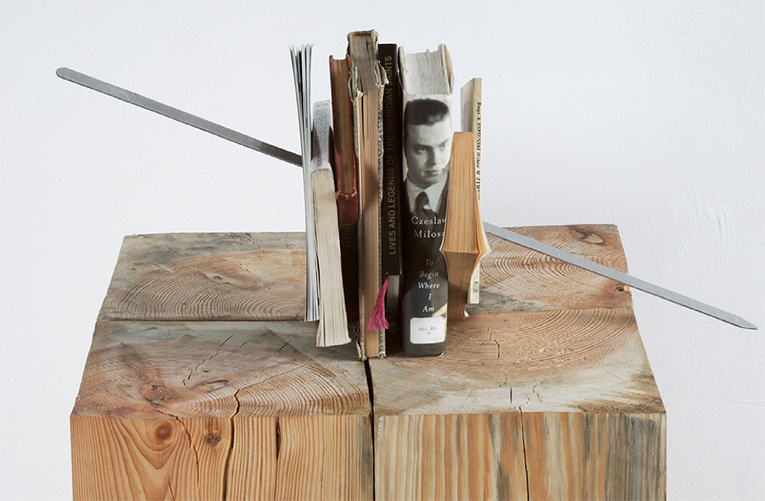

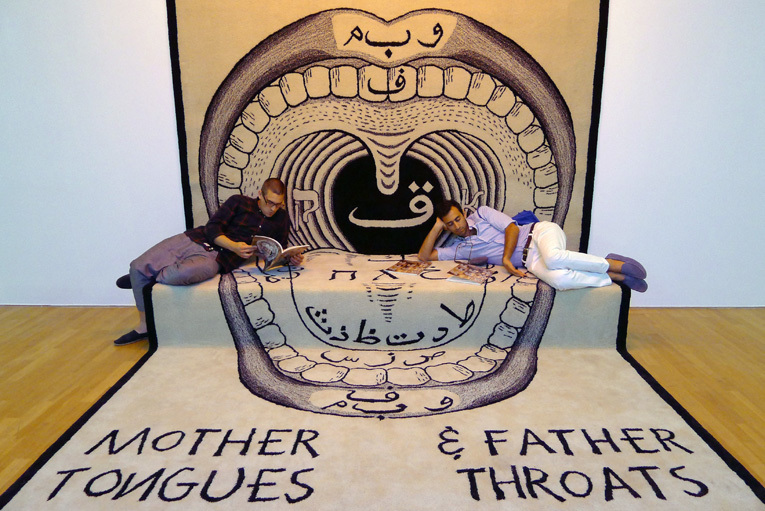

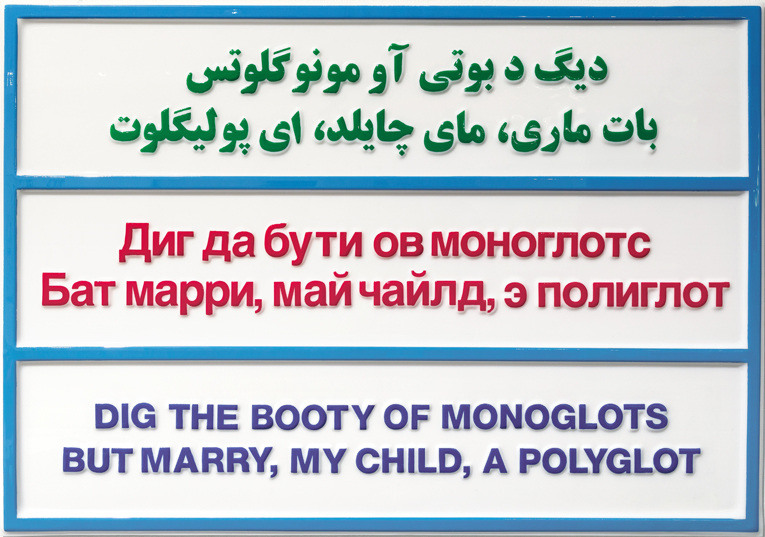

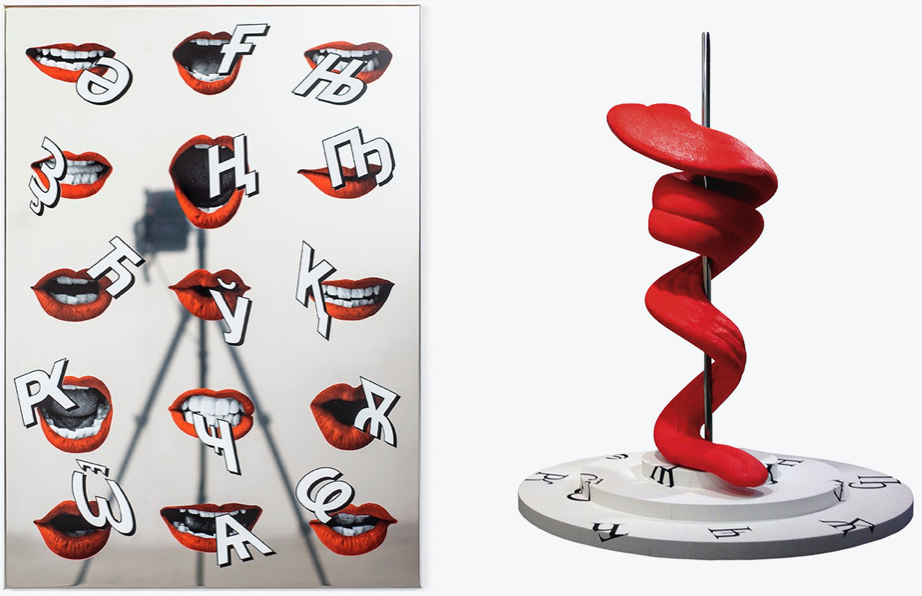

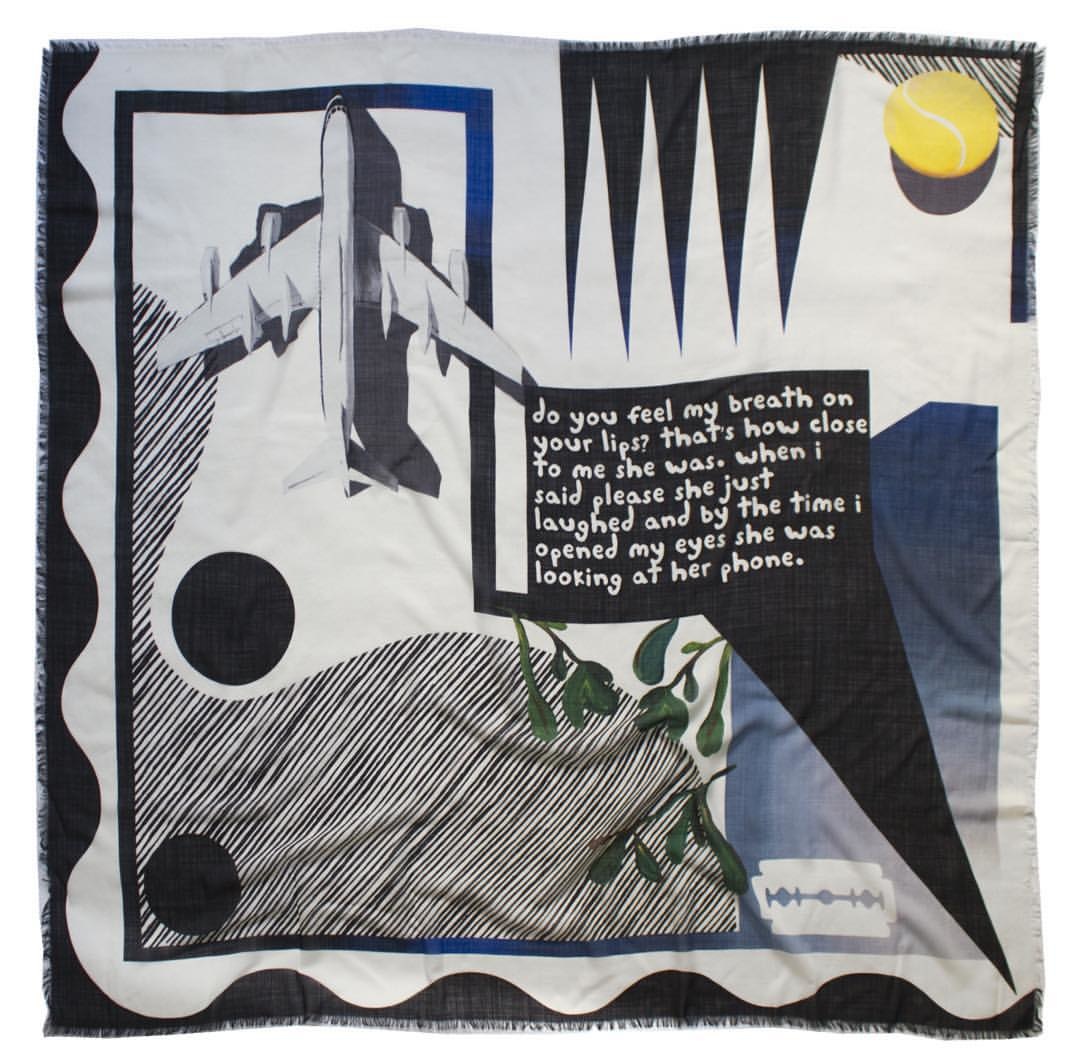

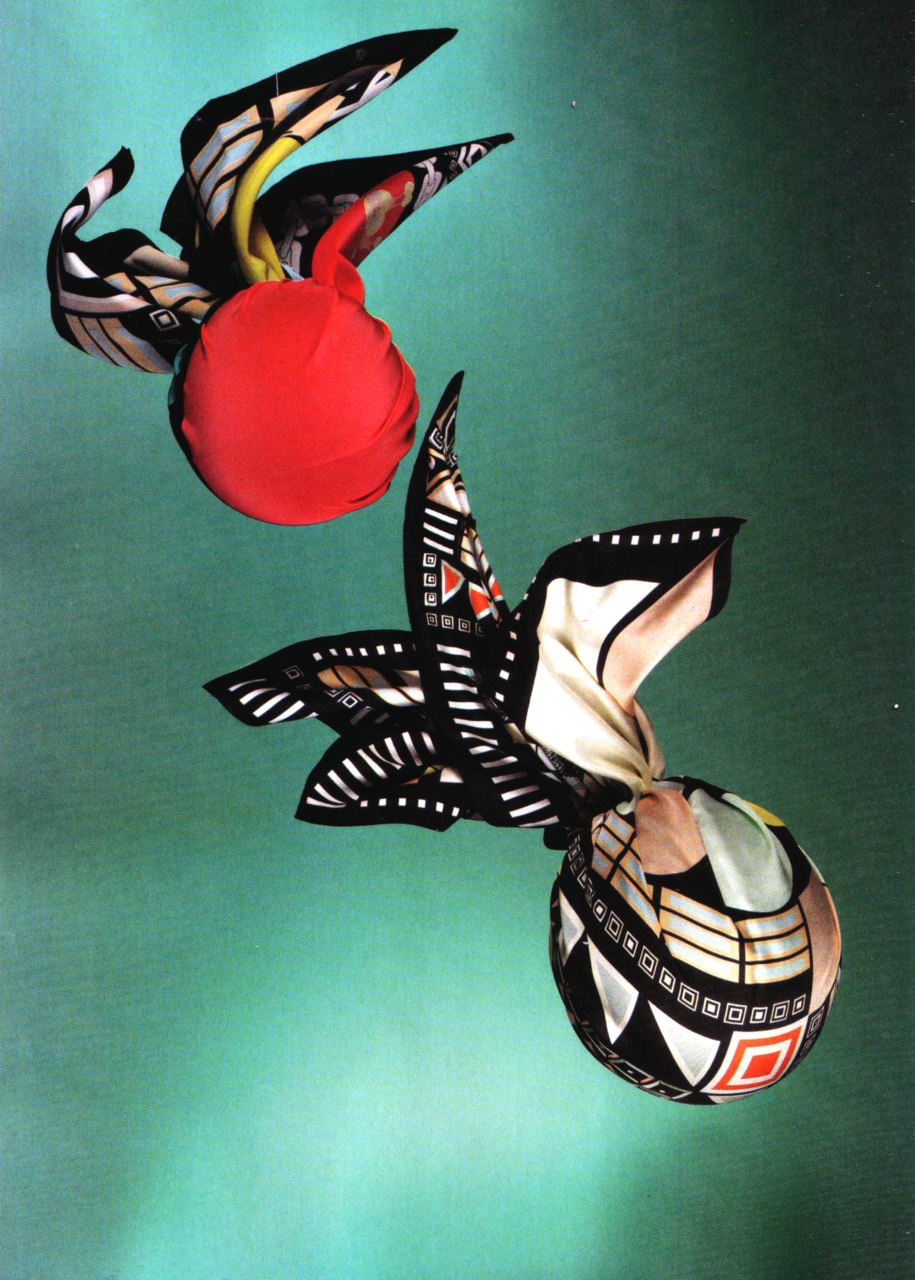

All creations: Vaqar

Text: Anahita Vessier

http://vaqar.com/

https://www.instagram.com/_vaqar_//

Share this post