SLAVS AND TATARS, A new vision of Eurasian Art

Slavs and Tatars is an art collective founded by Kasia and Payam, a Polish-Iranian duo, who dedicate their work to an area east from the former Berlin Wall and west of the Great Wall of China. Anahita’s Eye follows their work for a long time and had the chance to interview them while they were preparing their exhibition “Afteur Pasteur” in New York at the Tanya Bonakdar Gallery.

Why the name “Slavs and Tatars”? And why this devotion to an area, as you describe “east of the former Berlin Wall and west of the Great Wall of China”?

Usually a name is chosen for what one represents or who one purports to be. We decided on Slavs and Tatars for the opposite reason: for that which we are not. Our name is a mission statement of sorts: to devote ourselves to a geography that is equally imagined as it is political, to a region that falls through the cracks of our amnesiac floors.

“It happens to be largely Muslim but not the Middle East, it is largely Russian-speaking but not Russia, and though largely in Asia, only a small part (Xinjiang) has historically been under Chinese rule.

There’s of course an element of humour in the name too. We founded Slavs and Tatars in 2006, shortly after the entry of the new member states in 2004 into the European Union. If you recall, there was quite a bit of prejudice, if not hysteria, about this ‘other’ Europe, namely Eastern European states joining what Europeans had imagined themselves until then an exclusive club. There was the infamous Polish plumber, the Bulgarian builder, etc…The name Slavs and Tatars clearly plays up this fear–both in a contemporary and historical sense–as if there were hordes waiting to rape and pillage à la Braveheart.

Our name–Slavs and Tatars–is not an identity, it marks the collapse of identity. Even between these two terms, “Slavs” and “Tatars” there is a whole story of confluence and tension. It is only by accumulating several identities–and negotiating the tensions between them–that one can begin to move beyond the reductive and brittle identity politics which continue to plague us.

Explain me your creative process. What are your inspirations? Why did you finally chose sculpture/object art as your main tool of expression?

Sculptures, installations and exhibitions are only one of our three activities and by no means the main one, alongside publications and lecture performances.

We currently present 2-3 lecture-performances per month in different venues: from universities to art institutions. We generally work along three-year cycles. The first two years are dedicated to research on a given subject of investigation: first bibliographic research, for example, into Turkic language politics or the medieval genre of political advice literature known as “mirrors for princes” followed by field research, say, to Xinjiang to experience more affectively the ideas that we’ve been exploring more analytically. Then the crucial question arises:

“What are we as artists bringing to the table that is distinct from the work of others, policy makers, scholars, activists…?

The translation or transformation of this research into art work is perhaps the most difficult. In the beginning, we worked exclusively with print: if someone wanted to engage with our work, she had to read. There are few things less pleasant, less considerate to the public than putting something to read on a wall. Even though the practice proliferated – to include sculpture, installations, lecture-performances – walls somehow did not become any more attractive in our eyes. If we live in an age of visual glut, then we are amongst the (many) guilty enablers!

Among the three axes of our practice, the lectures and publications articulate a series of concerns that the sculpture, installation, the material art work with a capital ‘A’ must disarticulate. That does not mean to remain silent: rather to undo, unravel these very ideas, like a loose thread of a sweater.

Do you have a favorite quote that inspires you?

“Quit this world. Quit the next. And quit quitting”

–Thomas Merton

Does each of you have a very defined role in “Slavs and Tatars”?

Yes, but we edit each other rigorously.

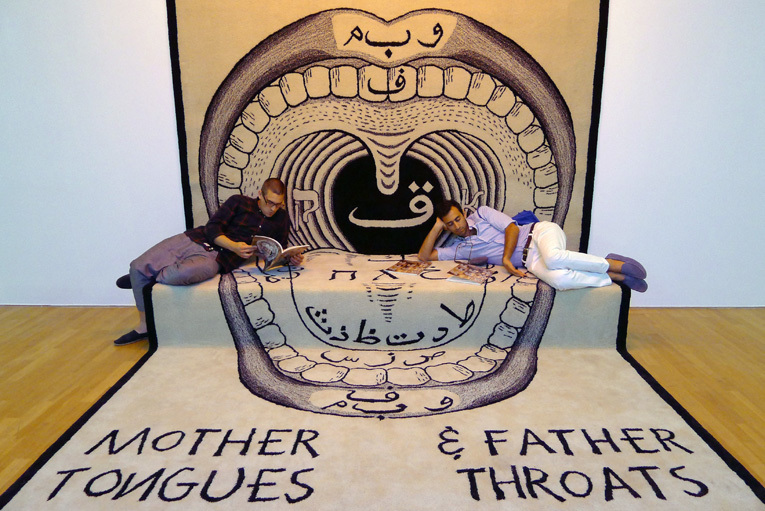

In many of your installations you invite people to interact with it, touch it, sit on it, lie on, discuss on it. Is this direct confrontation and personal experience that people have with your artwork an important part of your artistic concept?

Definitely. It is also a commitment to the idea of contemplation in spaces devoted to culture. Too often, the only place to sit in a museum is the cafe, or the rare bench in front of a masterpiece. If art is to play a transformative role, and not only an educational and entertaining one, the venue of its activation must be more hospitable.

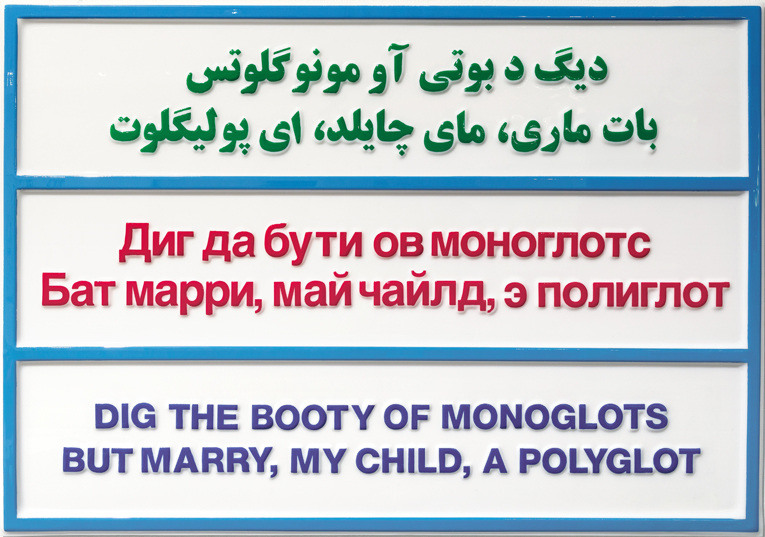

Slavs and Tatars speak so many different languages, Farsi, Polish, English, French, Russian etc. Language and the linguistic complexity is a very important subject in your work. Why this intense love for languages?

Translation becomes a form of linguistic hospitality, to quote Paul Ricoeur. We invite the Other into our language and the expropriating ourselves into the language of the Other. We are different people in each language: our sense of humour in French is not at all similar to that in Russian or Persian, etc.

“Language allows you to “other” yourself.”

Is humour an essential ingredient in your artwork?

Absolutely, it has always played a very important role in our work: as a disarming form of critique, as an extension of generosity, as an indication of infrapolitics: as defined by James Scott: the hidden transcript, the whispered stories.

“Every joke is a tiny revolution”

to quote Orwell, rather than the often confrontational, explicitly visible politics of the march, the news, or the state.

What are your future projects?

We’re currently preparing for our first show with our NY gallery, Tanya Bonakdar, on pickle politics, or a reconsideration of our relationship with the Other, via our relationship with the original foreigner: the microbe and bacteria. We’re also working on a mid-career retrospective for 2017-2018, between Warsaw, Vilnius, and perhaps Istanbul.

You have a very cosmopolite live, your art is shown at art fairs and exhibitions all around the world. Is there any special object that accompanies you on your trips around the world?

We try as much as possible to travel with fresh herbs – a bunch of tarragon, a couple stems of coriander – to soften the blow of eating en route in trains, planes and automobiles.

Slavs and Tatars, what comes to your mind when you think about Iran?

Mulberries

Credits:

All works by Slavs and Tatars

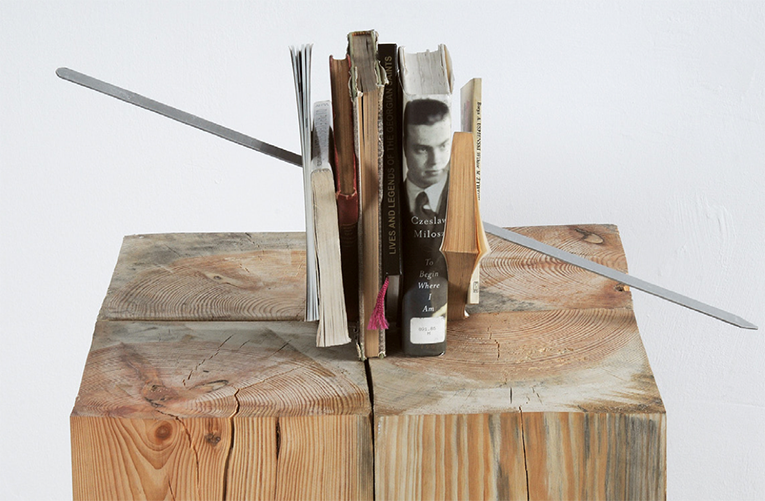

Kitab Kebab, 2016 – ongoing

Friendship of Nations: Polish Shi’ite Showbiz, published by Book Works / Sharjah Art Foundation

Mother Tongues and Father Throats, Moravian Gallery, Brno (2012)

Dig the Booty (2009)

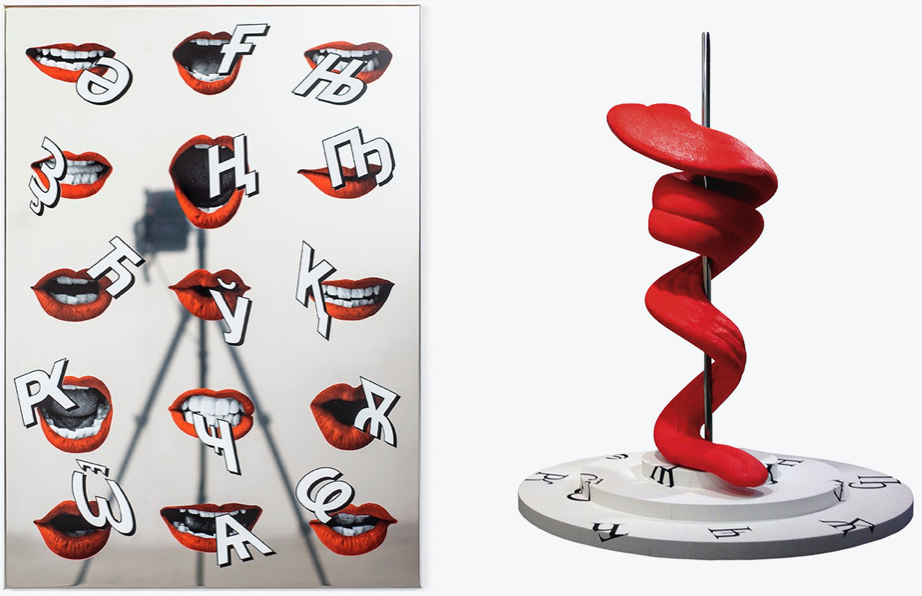

Pray Way (2012)

Installation view at Trondheim Kunstmuseum

left: Larry nixed, Trachea trixed (2015) right: Tongue Twist Her (2013)

Lektor, sound installation, Leipzig (2014-15)

AÂ AÂ AÂ UR, Skulpturpark Köln (2015)

http://www.slavsandtatars.com

Share this post