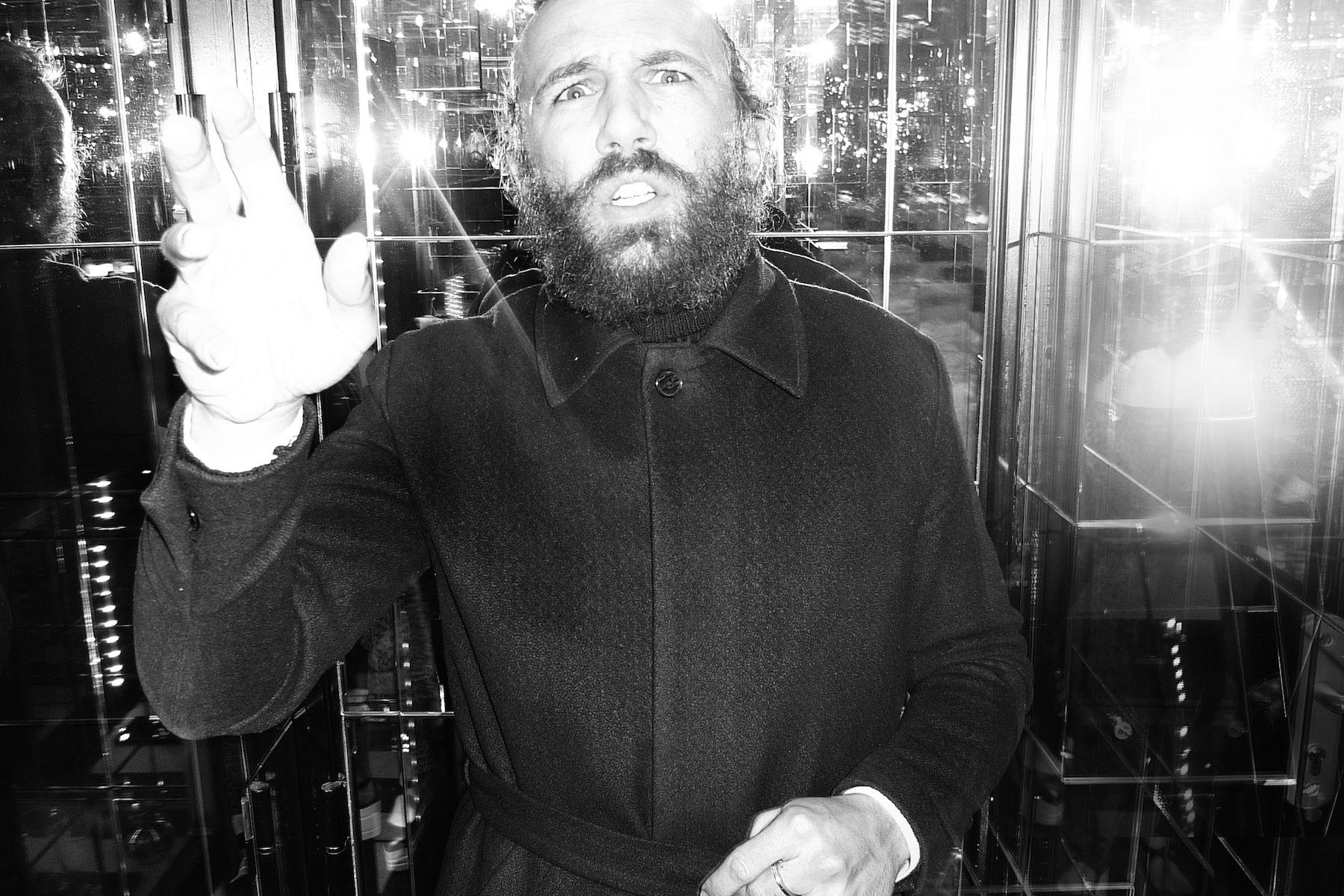

MATHIAS KISS, The artist with the golden hand

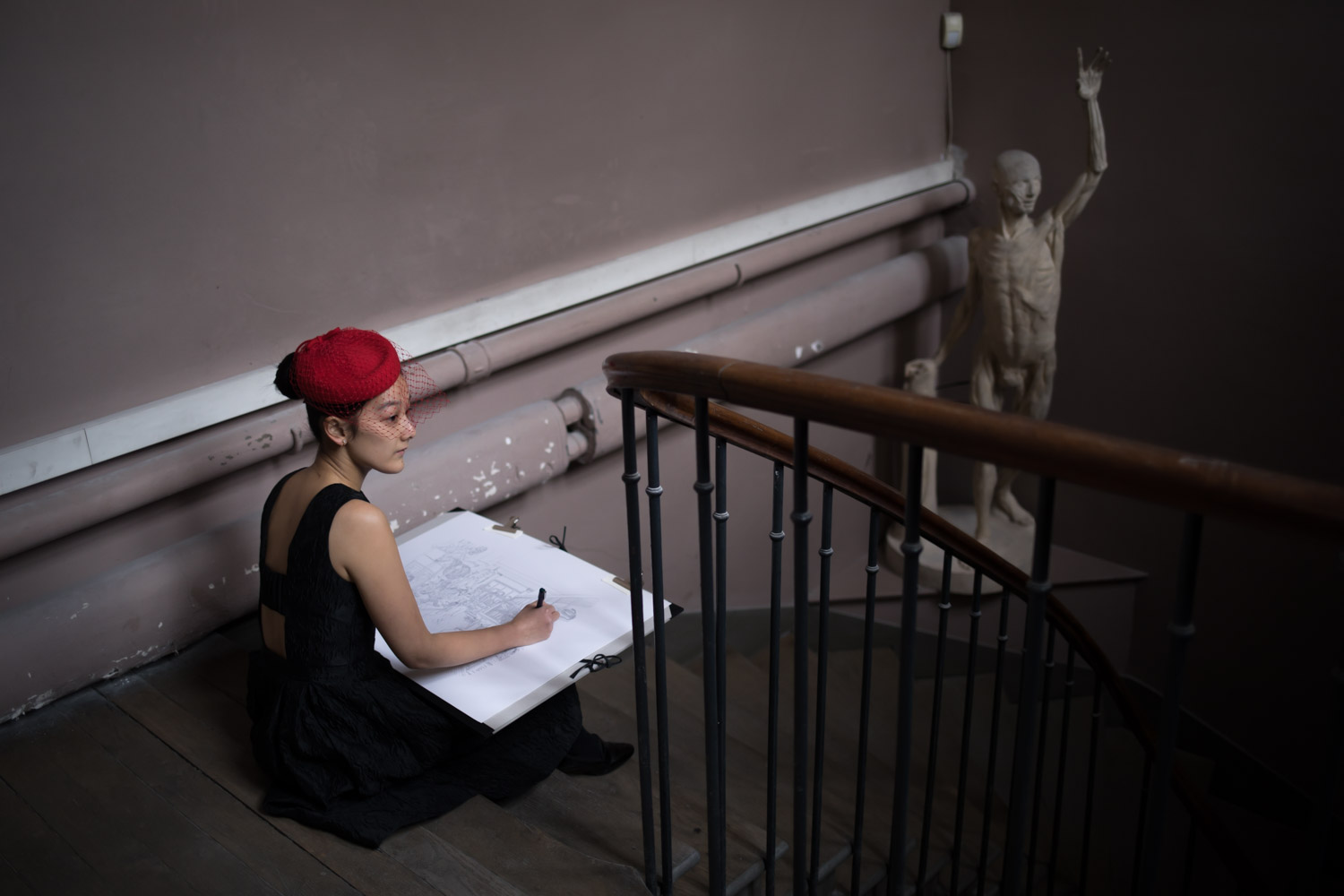

Mathias Kiss is a French artist, iconoclast and dandy with boundless creative energy. In his art he folds academicism to find new codes and to break down the barriers between disciplines by association French classicism and avant-gardism.

His extravagant and oversized installations are shown in the most prestigious galeries and museums such as the Palais de Tokyo or the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, and his artistic universe seduces luxury brands like Hermès or Boucheron.

When did you decide to become an artist?

I’ve started an apprenticeship as a painter and glazier when I was 14 years old. When I was 17, I’ve joined the Compagnon du Devoir where I’ve been working for 15 years. My dream was to study at the Academy of Fine Arts in Paris if I had the chance.

But finally all these periods in my life have given me the tools, skills and knowledge to do the work that I’m doing today.

My art is inspired by my life with all the traumatizing experiences.

What kind of trauma?

Which girl wants to go out with a construction painter!

Failing school when you’re 14 and starting a job when you’re so young is very complicated. Nobody was interested in a guy like me. Everybody was studying, doing a white-collar job, being a graphic designer etc.

It was really hard to feel alone and to be considered as an outsider.

How would you define yourself? Craftsman? Artist?

When I was with the Compagnons, my only goal was to become as good craftsman so my boss wouldn’t get angry and shout at me because the sky on the ceiling wasn’t perfectly painted.

I couldn’t even imagine to have thoughts like « Why not painting the sky red instead of blue? ».

Many years later I’ve managed to emancipate myself and get free from the rigid conventions and move towards art.

At the being of my career as an artist, people didn’t know what to think of my work, which category they could place it. Fortunately some trusted me and encouraged the others to buy my work.

Why this urge to break the rules ?

When you work for the Compagnons you grow up with a compass and a triangle which is symbolizing the rules. People of my age weren’t interested in my work. Too classic, too rigid, too dusty. I needed to break down these barriers, free myself from these technical and aesthetic conventions.

So I was wondering how it would be possible to preserve the historical codes of French savoir-faire and incorporate them and place them into a contemporary context.

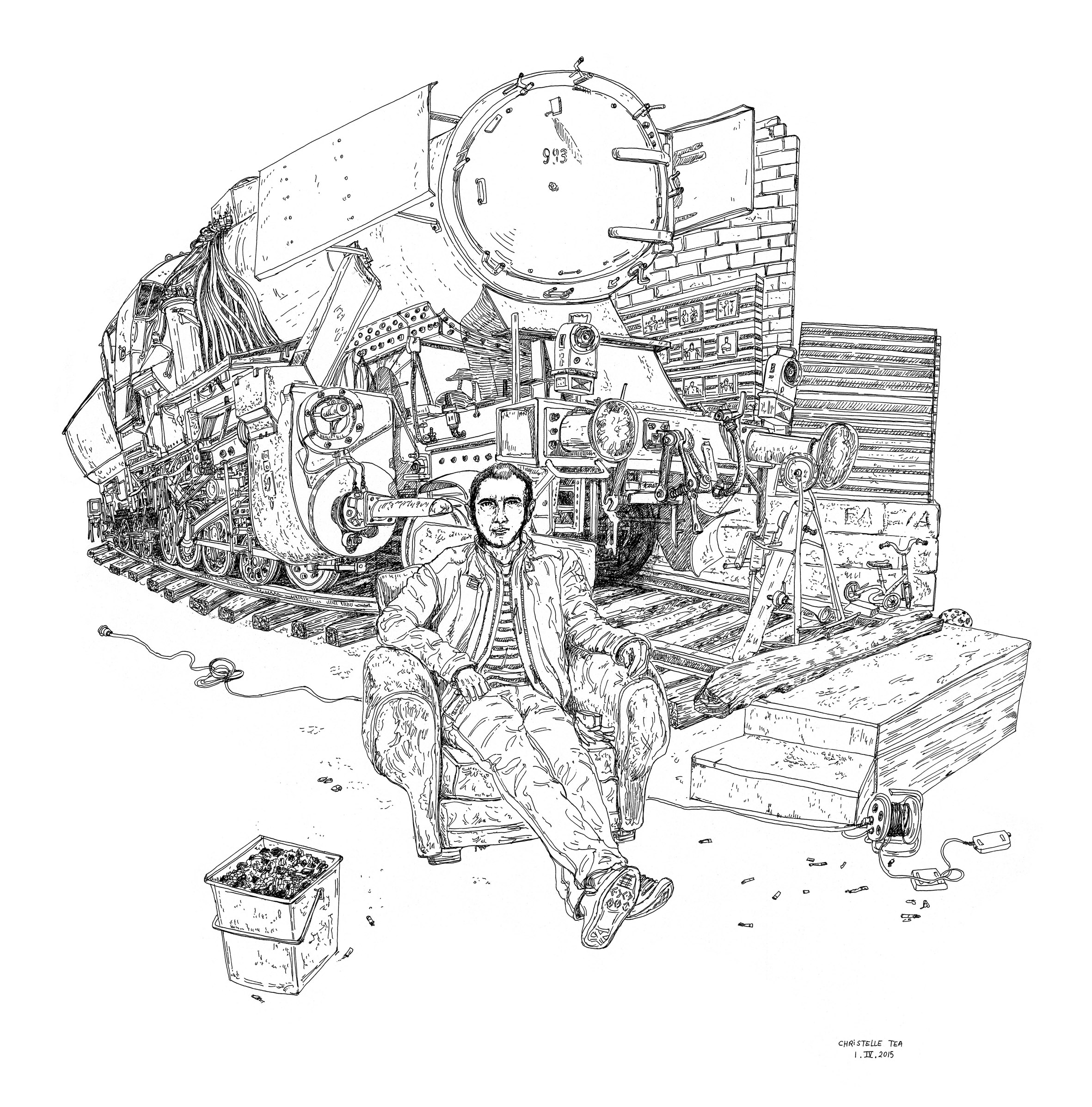

My work consists of two groups of artwork:

One is under the title « Sans 90° » which contains all the work inspired by the thought around the absence of the right angle such as the mirrors « Miroirs Froisées », the trompe l’oeil marble « Igloo » seat, the « Magyar » carpet.

The other group entitled « Golden Snake » gathers all the work that deals with experimenting with architectural elements of French classicism and questioning the artistic working process.

Why is gold such an interesting material for you as it takes a very important part in your work?

Gold is light, is life. It’s not only opulent, kitschy or outdated.

Gold allows to engage a conversation about power, for example the power of seduction of a woman enhancing this by wearing jewelry, or the power of men, who have always fought for possessing it.

Are there new challenges that you would like to face in your work?

As a Compagnon I’ve been working in all the important historical dwellings of the French Republic, such as the Comédie Française, Opera Garnier, Conseil d’État, and many others. Even though I had the chance to work in those sumptuous places, I was very unsatisfied with my work and decided to turn to contemporary art.

So a perfect mix of both experiences would be to build installations for public spaces, a kind of tribute to Paris, the city of sights and museums.

I’m thinking for example of adapting my installation « Golden Snake » that has been exposed at Palais de Tokyo for an urban environment where kids can climb on it or people can sit on it.

That would be an interesting project and a real challenge.

Aren’t you feeling anxious when you’re standing in front of those wide empty spaces at the beginning of a project?

The bigger the space, the more I dig it! To me it’s like a huge white sheet of paper where I can let my artistic imagination run wild.

You’ve done a lot of thai boxing and you have been even participation in official competitions until you were 30. During your exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo you’ve invited the world box champion Patrick Quarteron to have a little box match together in front of your installation « Golden Snake » for the magazine Numéro. What have art and boxing in common?

It’s true that people don’t see the points that these two worlds have in common.

A boxer is a guy, standing half-naked on a stage trying to win and being applauded by the audience that is standing around and watching. This is total narcissism and exhibitionism, isn’t it! The need of love and standing in the lime light is not far from an artist.

Both are also taking risks, accepting knocks and leaping into the unknown.

What’s your next project?

A carte blanche project for the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Lille for April 2019.

What comes to your mind when you think of Iran?

The sumptuous festivities that were given by the Shah of Iran to celebrate the 2500th anniversary of the Persian empire. It’s crazy that people still talk about it. It almost became a kind of monument, a very strong symbol.

Credits:

All photos by David Zagdoun

Except:

Featured image of Mathias Kiss on Home by Wendy Bevan

Photo of Mathais Kiss and Patrick Quarteron by Stépahne Gallois for Numéro

http://www.mathiaskiss.com

Text: Anahita Vessier

Translation: Anahita Vessier

Share this post