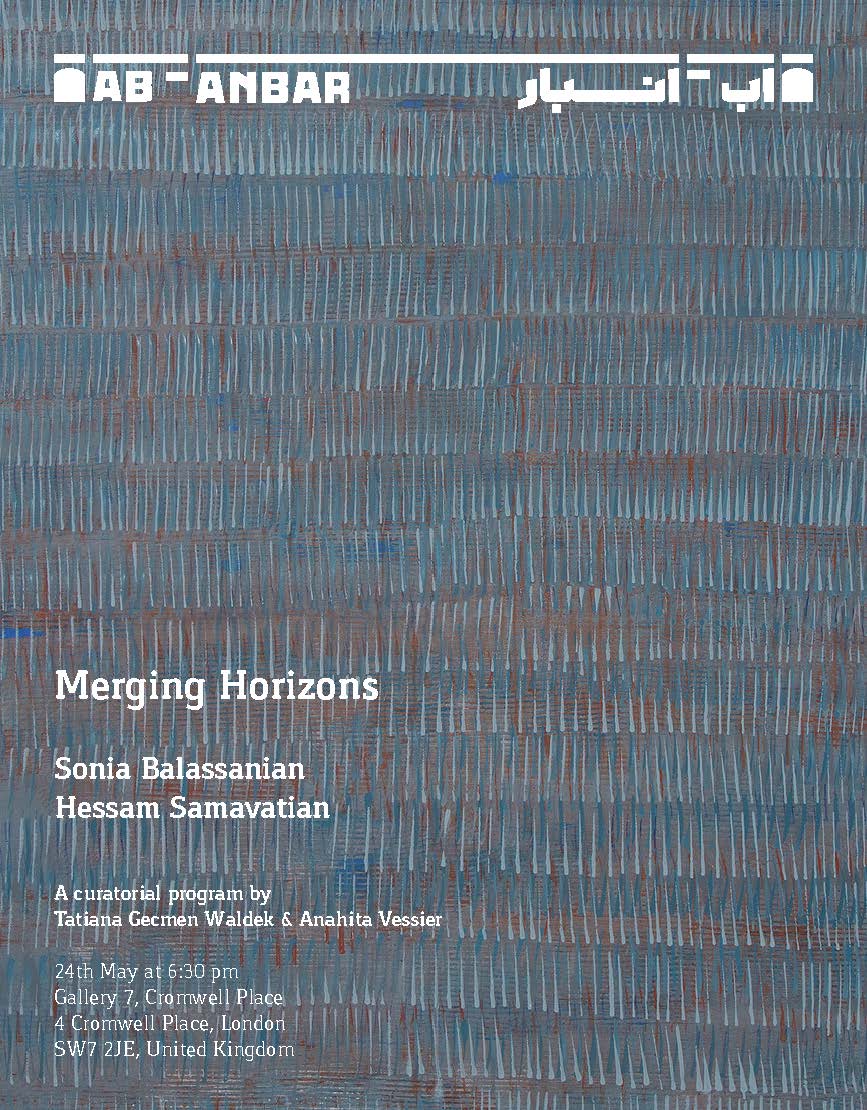

HORMOZ HEMATIAN & ASHKAN ZAHRAEI, Electric Room, art under high tension

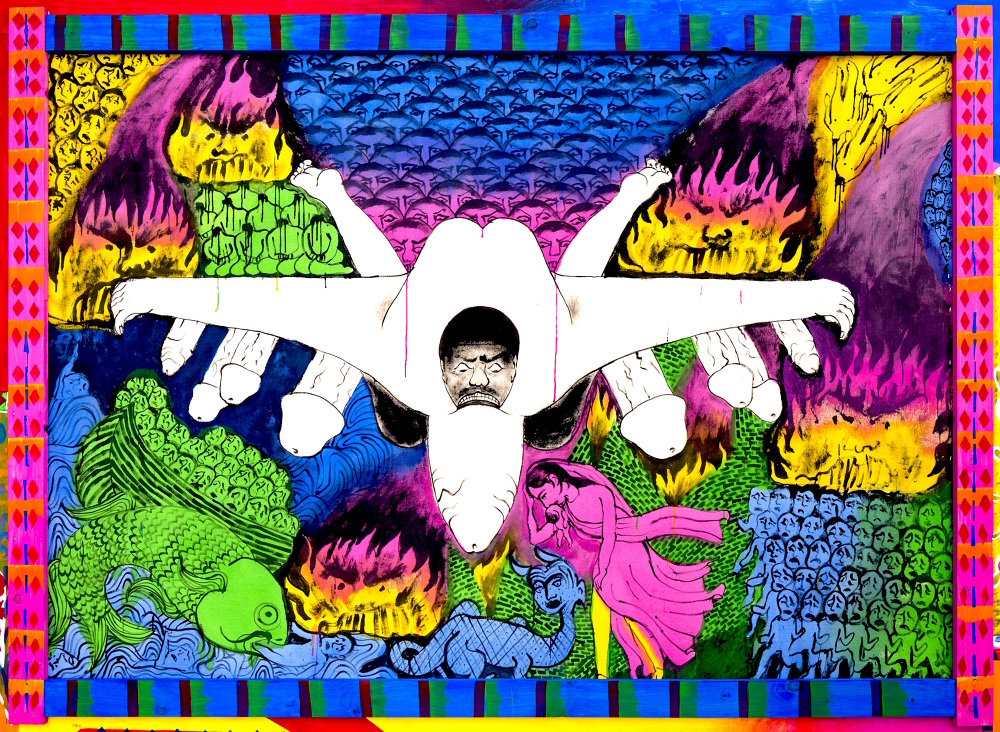

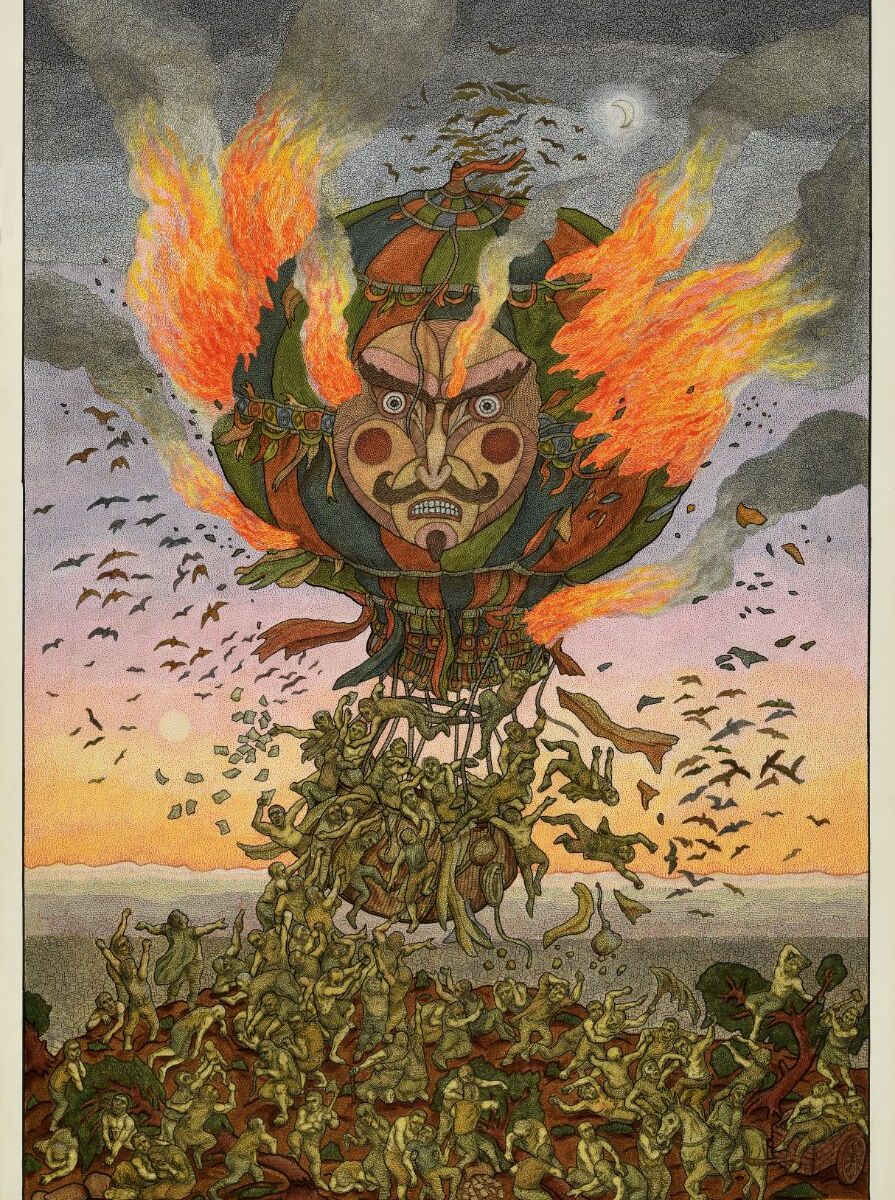

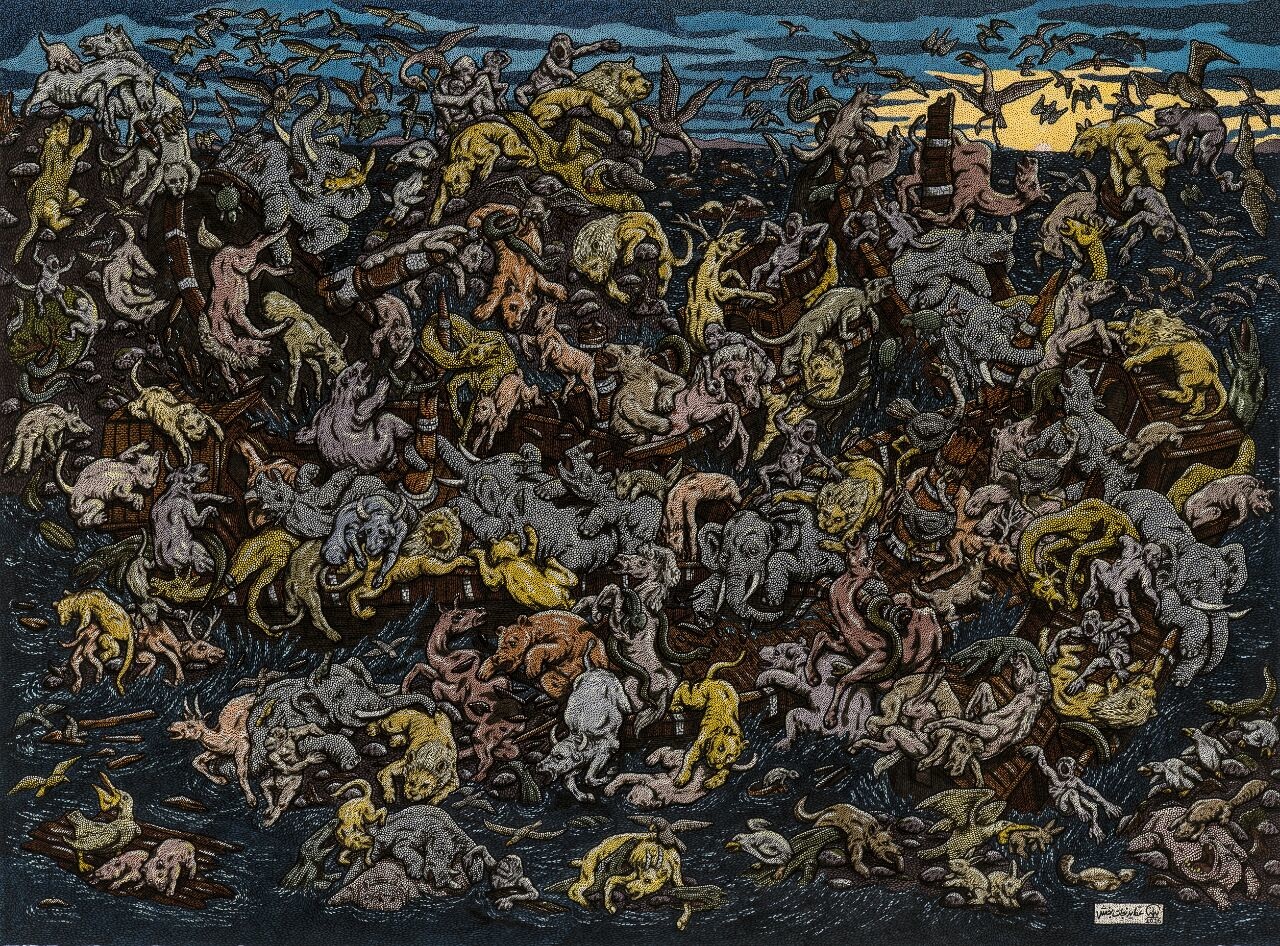

Tehran has a rich and vibrating art scene with highly talented artists, many of them were born after the Islamic Revolution.

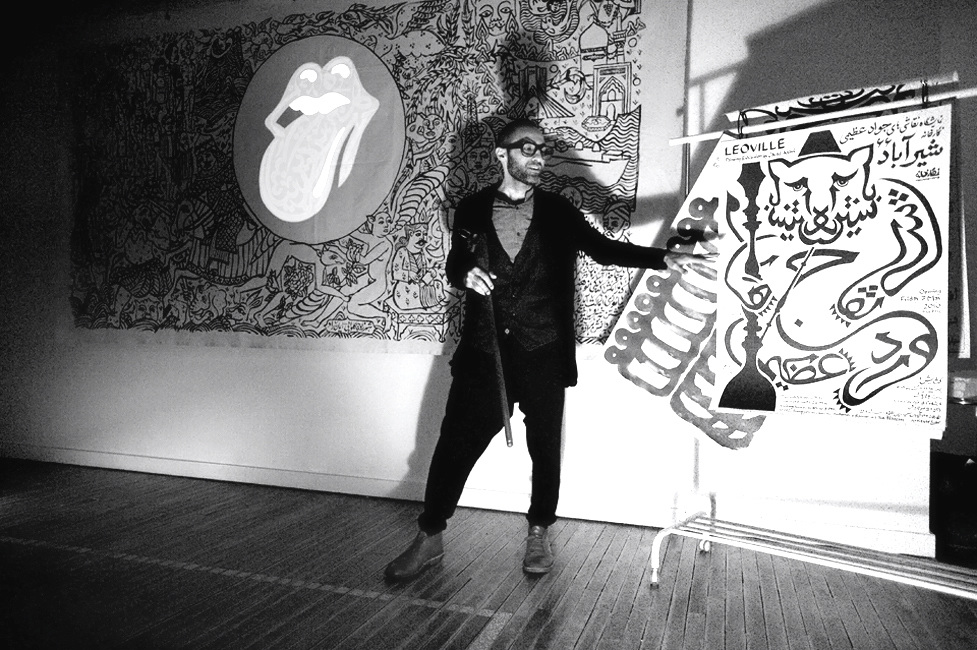

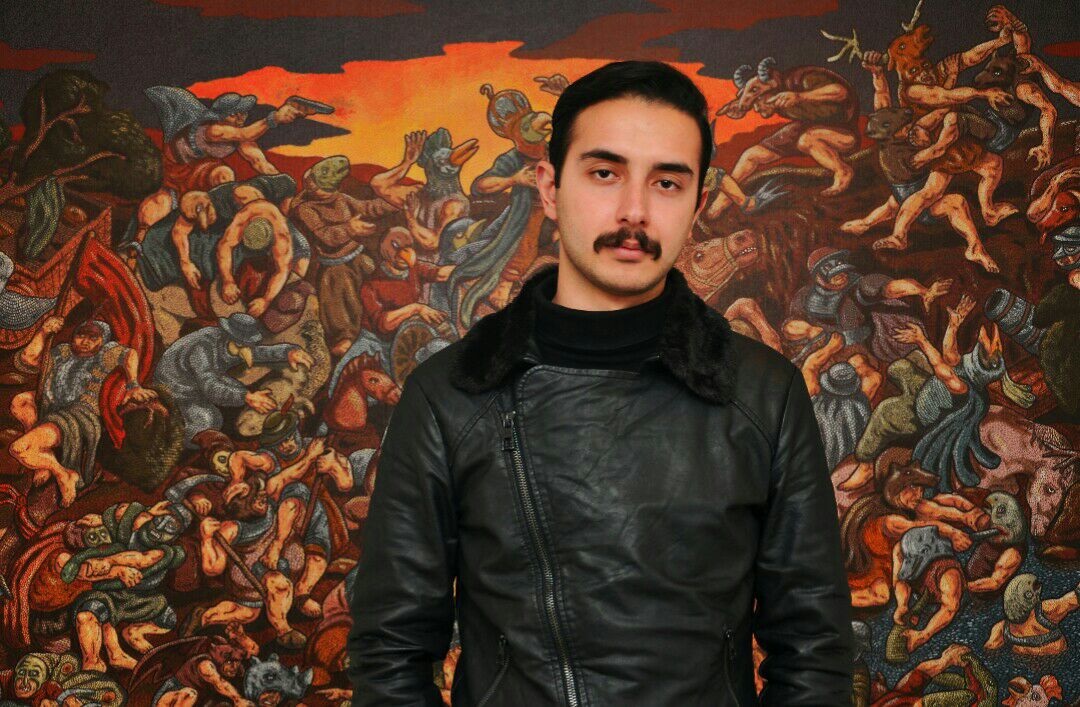

Hormoz Hematian, founder and director of Dastan Gallery, one of the edgiest art spaces in the Iranian capital focusing on contemporary art, and his friend Ashkan Zahraei, Dastan’s curator and communication manager, travel constantly between Tehran and the most important art fairs around the world to promote the work of their artists and to develop international collaborations.

These two workaholics and unconditional art lovers have a thousand creative ideas in mind, are not afraid of any challenge and have launched “Electric Room” in 2017, which is certainly one of the craziest, most intense and ambitious art projects that makes Tehran a true reservoir of creativity and one of the most interesting and dynamic spots for contemporary art.

‘Electric Room’ is a very interesting and challenging art project that you have both developed and introduced to the Iranian art scene. How did this idea start?

AZ: Tehran has a very small art community. So through my work as a writer as well as a curator, both through working at Dastan and independently, I met a lot of artists who wanted to do art installations but there was no space in Tehran for experimental projects.

So that’s why Hormoz and I had the idea to launch the art concept ‘Electric Room’.

The concept was to showcase 50 experimental art projects in 50 weeks, introducing each week a new project and usually a lesser-known artist. So, it has a precisely defined beginning and end.

That’s a very ambitious and crazy project!

HH: Yes, the challenge was enormous! It’s more than some galleries show in five years.

Having three other galleries in Tehran, I was missing the spontaneity of doing a show. So Electric Room allowed us to give back and find again the romance of art.

So, in June 2017 we opened this temporary exhibition space, not bigger than 30m2, in downtown Tehran, right next to the Faculty of Art and Architecture, and within minutes of walking to the Faculty of Fine Arts and many of the city’s other cultural or artistic institutions.

There are a lot of students, so the vibe of this area is really good and dynamic.

We called the project Electric Room because one wall is almost entirely covered with electric switchboards and control units. It’s a very cool and unusual place.

AZ: Luckily we’re both workaholics!

The project was amazing and so intense for so many months. We wanted to offer people a unique experience.

We had only one day to take down an exhibition, repaint the walls and install the new show. And this every week, for 14 months. It was such a crazy rhythm!

And how did the Iranian audience react on this concept?

HH: The reaction was fantastic!

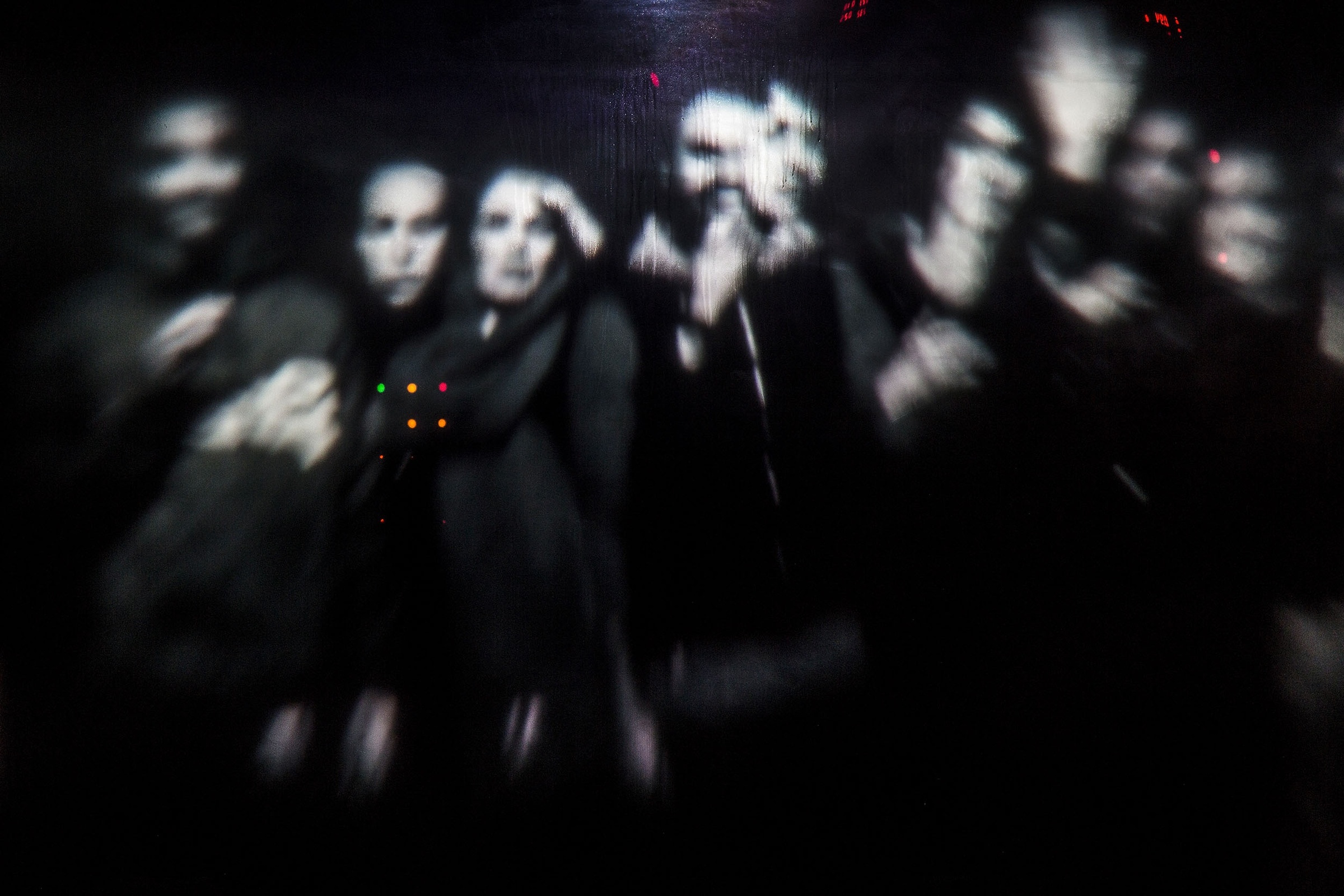

At each opening the ambiance was so vibrant, and literally « electric ».

We had so many people coming, that there was not even enough space inside the gallery for all the visitors.

And what kind of audience came to the openings?

HH: The right people. Young people, art lovers, potential clients, people who weren’t normally into going to galleries but loved the vibe and were intrigued by the space.

Each opening took 4 to 5 hours.

AZ: We were also inviting other galleries to show them the artists.

The fundamental idea of Electric Room was to be spontaneous, open, accessible and generous.

Showcasing 50 art projects of 50 different artists in 50 weeks is quite a challenge. How did you constantly find new artists?

AZ: We were focusing on several different types of projects:

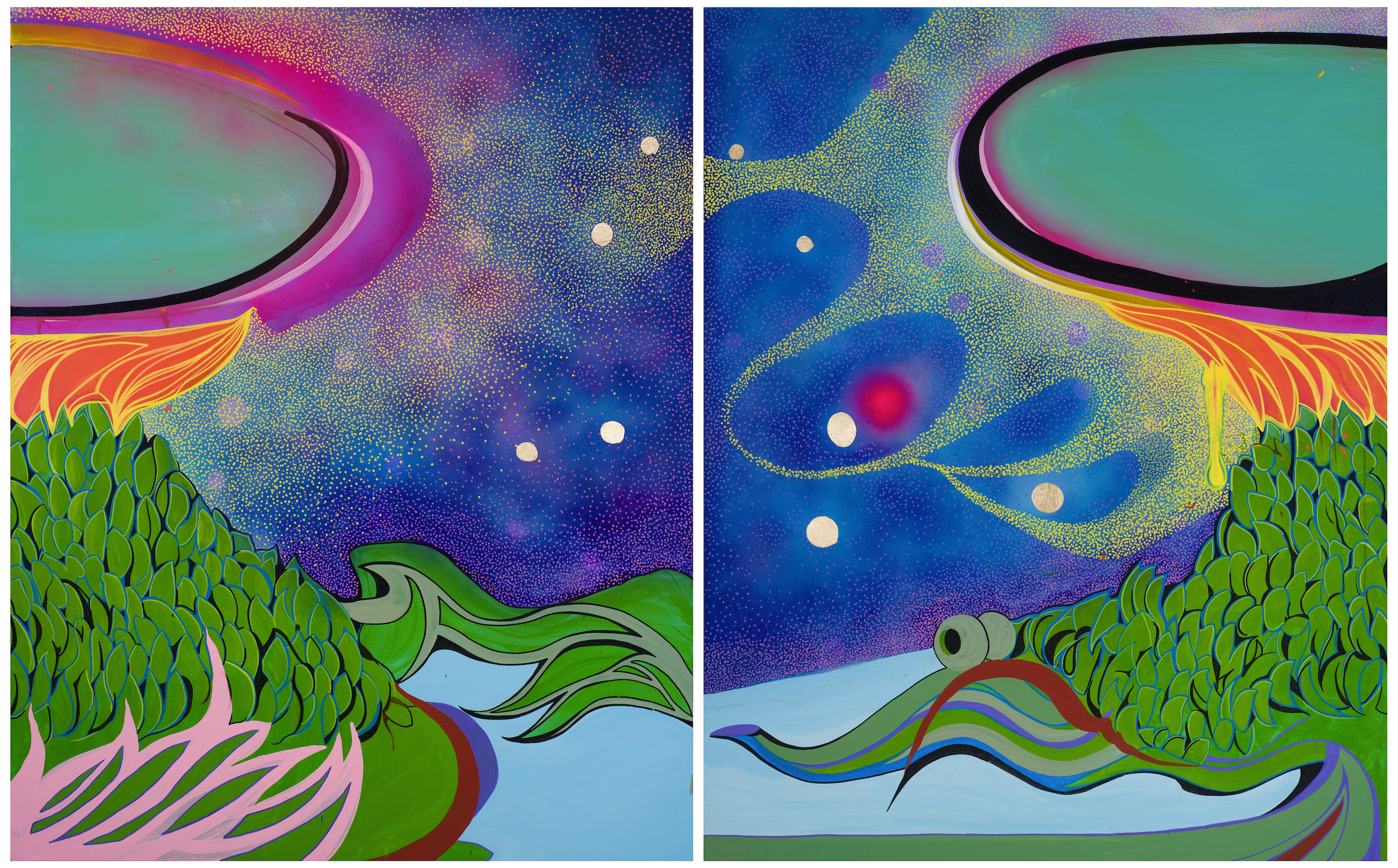

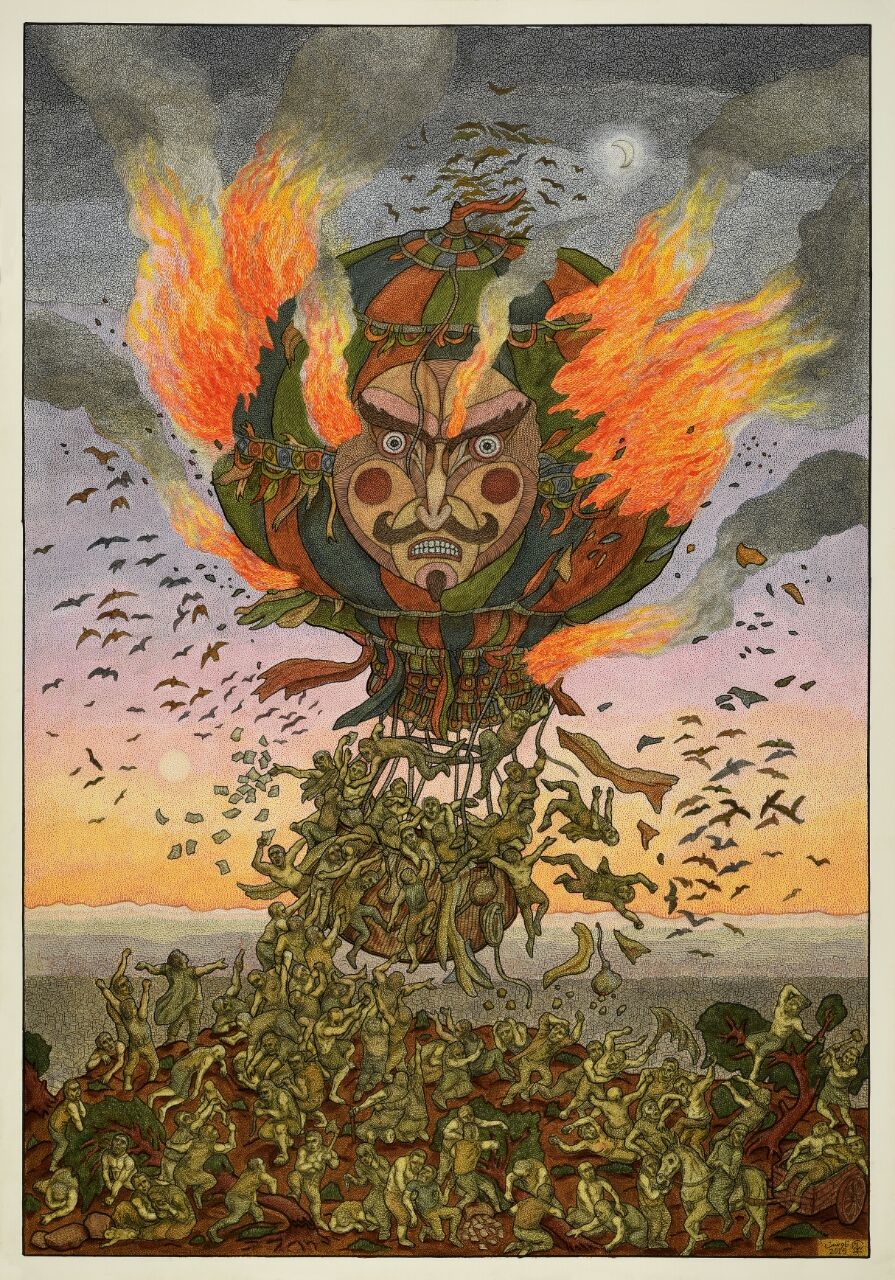

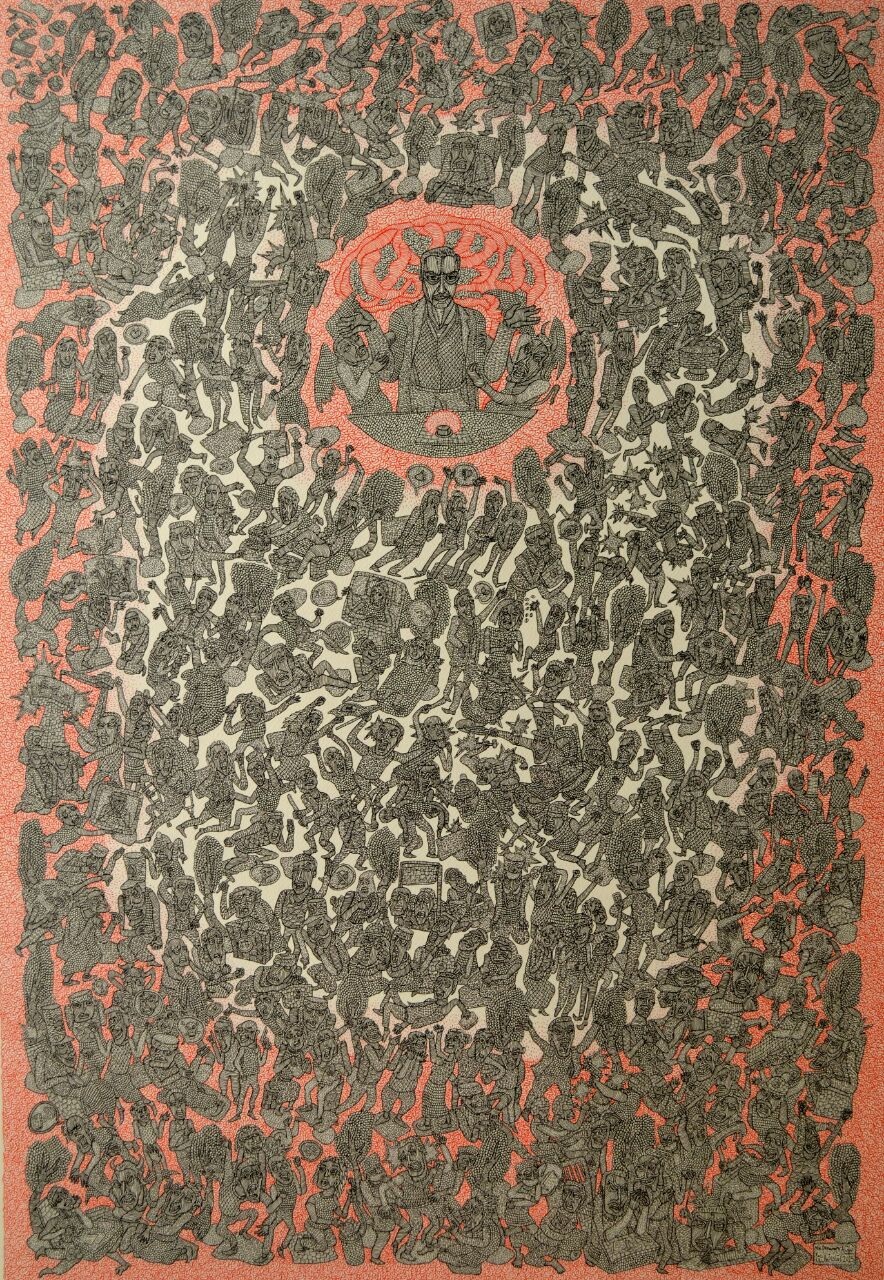

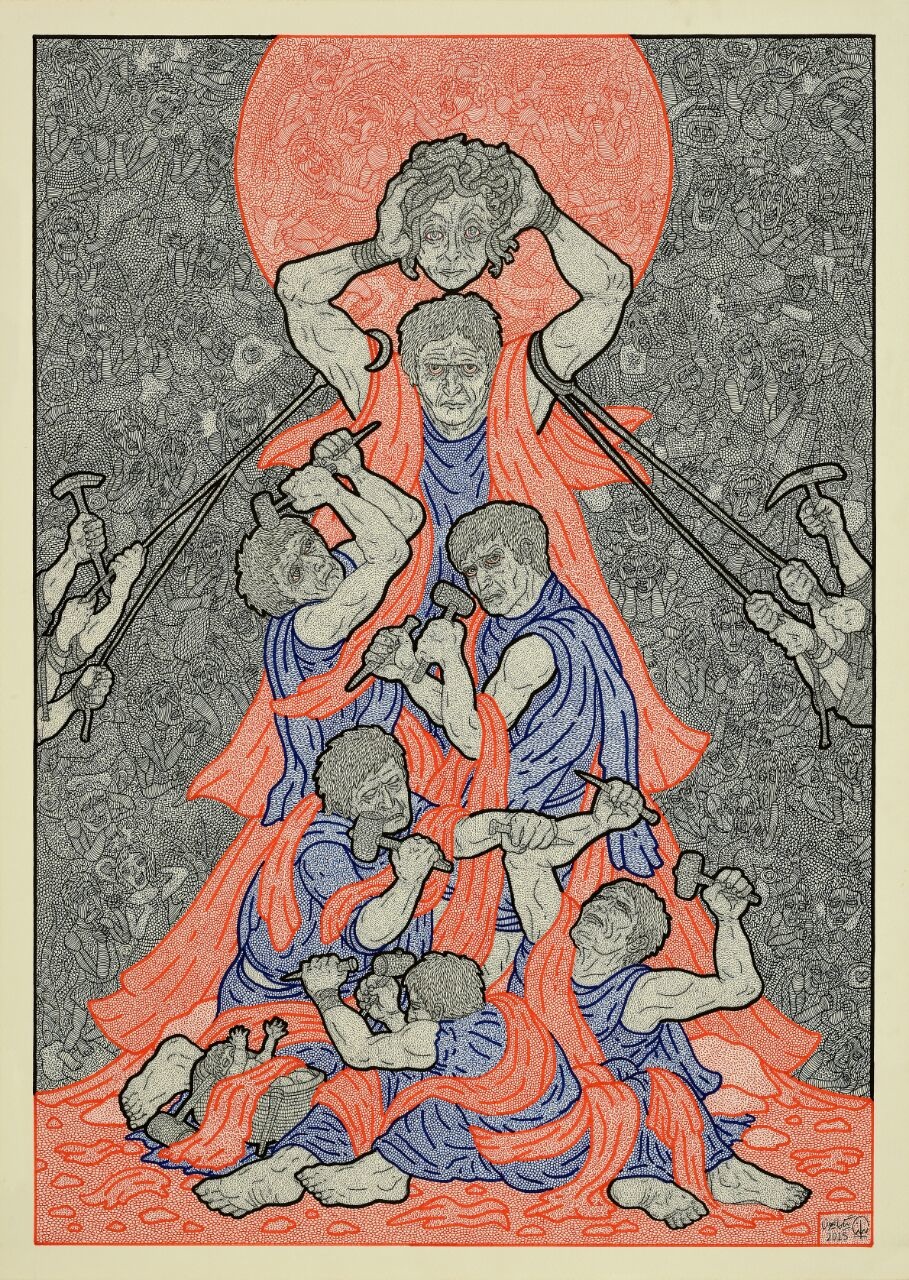

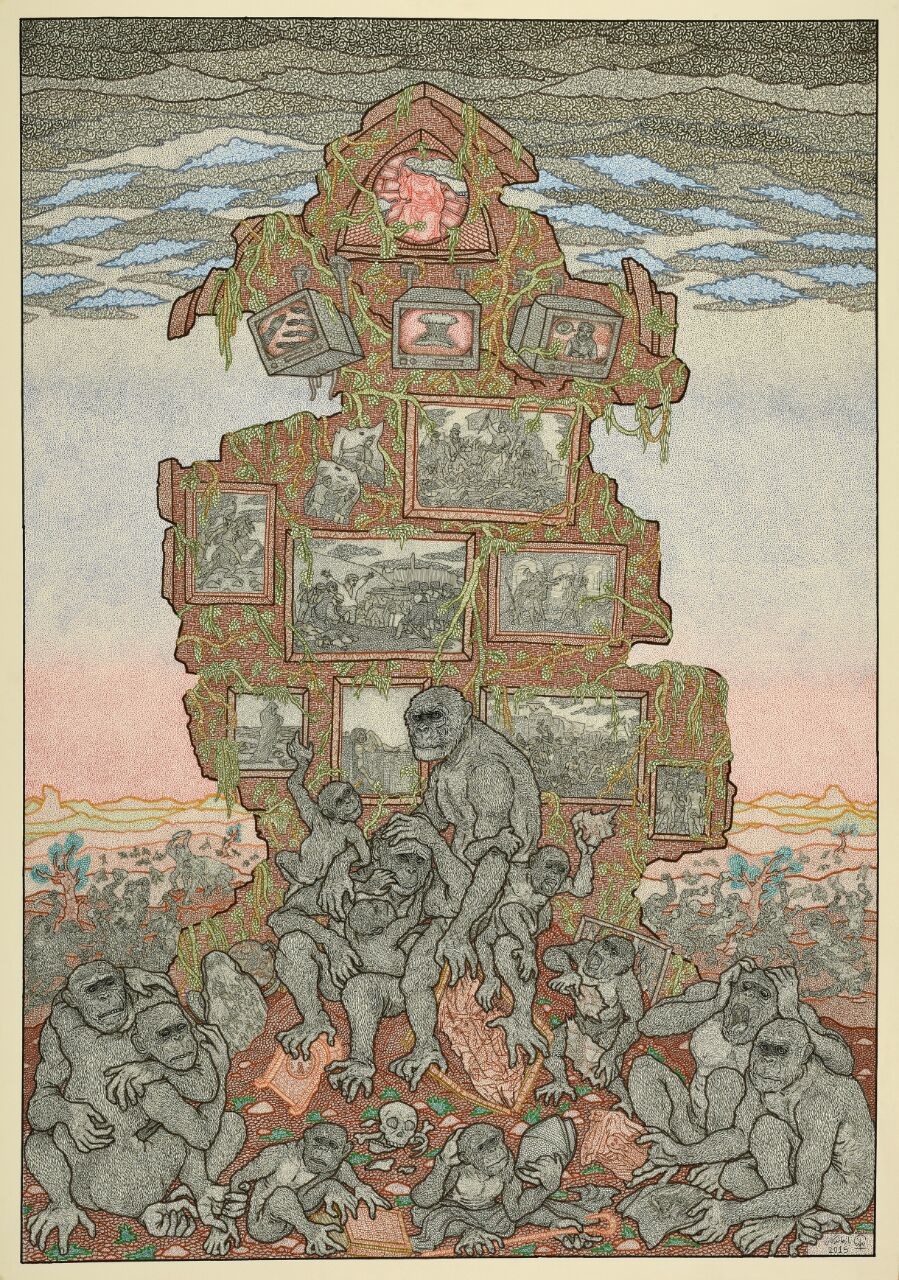

Installation projects, single-piece exhibitions, photo, video or multimedia projects, and also archival projects, like the « Tehran UFO Project ».

I’m a UFO enthusiast, so this show was an archival presentation of documents, articles and films relating to the historical incident from 1976 when UFOs have been seen over Tehran. I really like the idea that a non-art project becomes art.

HH: At the beginning some artists were quite skeptic because it’s a very unusual way of presenting art, they didn’t want to take a risk. So we had to start with the ones who trusted us.

AZ: That’s why we did our first few shows with artists that we already worked with at Dastan, including Sina Choopani, Mohammad Hossein Gholamzadeh, Meghdad Lorpour, and others.

These artists already had their followings and showing their work created more trust for other artists we wanted to work with.

Among those artists that you were showing some are Iranians who live and work abroad. Why is it still important to them to show their work in Tehran at your gallery?

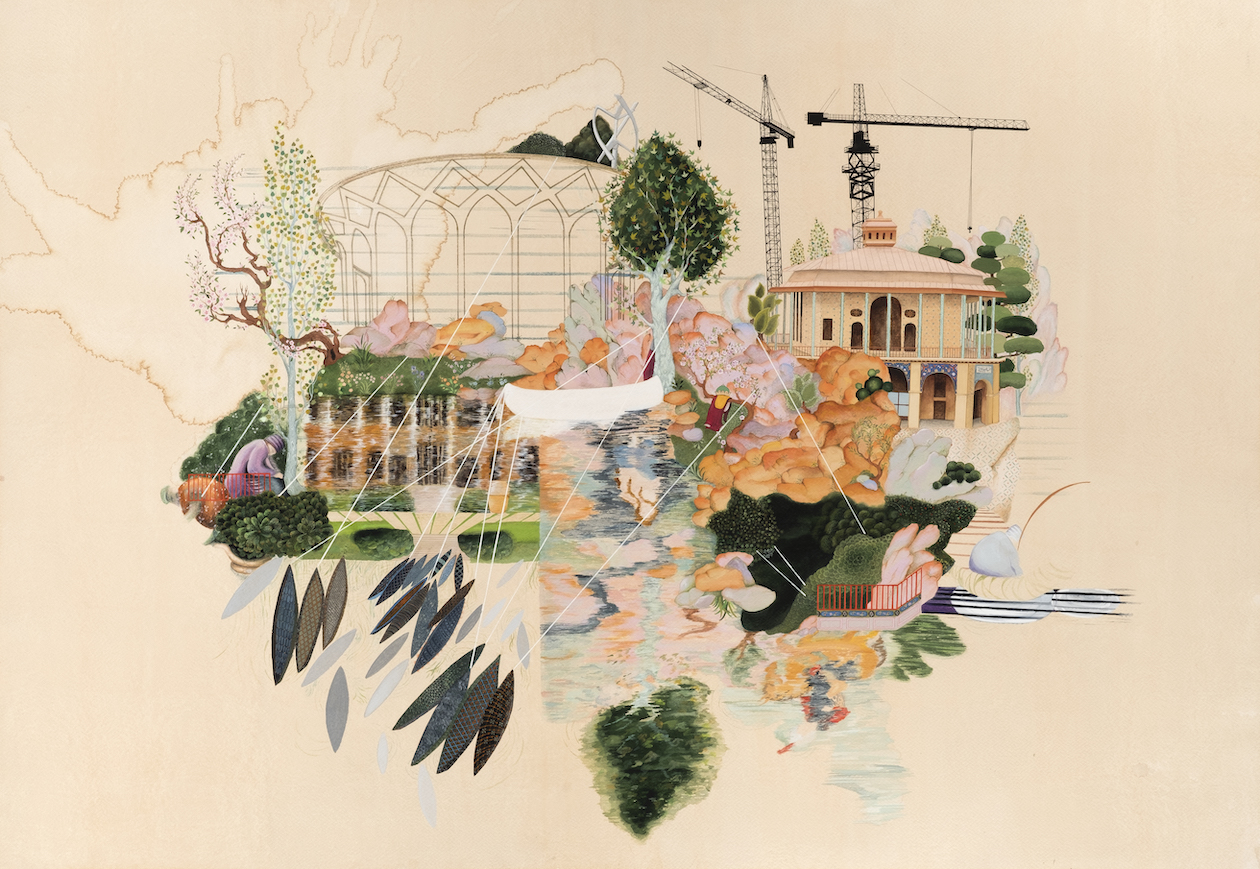

AZ: Electric Room created an opportunity to exhibit one’s work among a much wider scope and a more detailed program.

Many of these artists chose to exhibit at Electric Room because they wanted to be part of the experience and the program.

You’re working on such high-level art projects with Electric Room and Dastan Gallery and have gained a great reputation in the international art scene. But where does this love for art initially come from?

AZ: For me, visual art is a combination of my academic background (writing, critical theory) and a practical touch.

As much as theory and literature can give insights into the world, art gives me greater opportunities for communication and dialogue.

HH: My grandfather was a general before the revolution; after the Shah was overthrown, he left the army, turned towards painting and became a self-taught, amateur artist.

Whenever I went to visit him in his house in Khorasan, there was one room for his paintings, another one for his calligraphies and one for his instruments.

There was a certain magic to it. And I saw how art saved his life.

Did Trumps’s policy put an end to the Iranian art boom?

AZ: No, serious artists will always find a way to express their ideas. If there is no high-quality paint or paper in the stores anymore, they will use cheaper one but this won’t stop them from being creative, being an artist.

Living such an intense experience for 50 weeks, how did you feel during the last show of Electric Room?

HH: Very emotional.

AZ: I was unsure how to feel in the beginning, but the last day was indeed quite sad. As much as I was sure we needed to end what we had started, letting go felt very difficult.