Contemporary art in Iran

We’re in Tadjrish, in the very hype northern part of Tehran where the chic people of the city meet.

After getting out of the car, I need to stop for a second and enjoy just one more time the view that I love the most of Tehran, the snow-covered Elburz Mountains watching over the city imperturbably. I enter this old building from the 30s and even though it’s quite run down it reveals still at certain spots its beauty from the past. A slight breeze of nostalgia is blowing through the staircase. While walking up the stairs, the sound of electronic music brings my attention back to the present and guides me to the studio of the artist Mimi Maryam Amini.

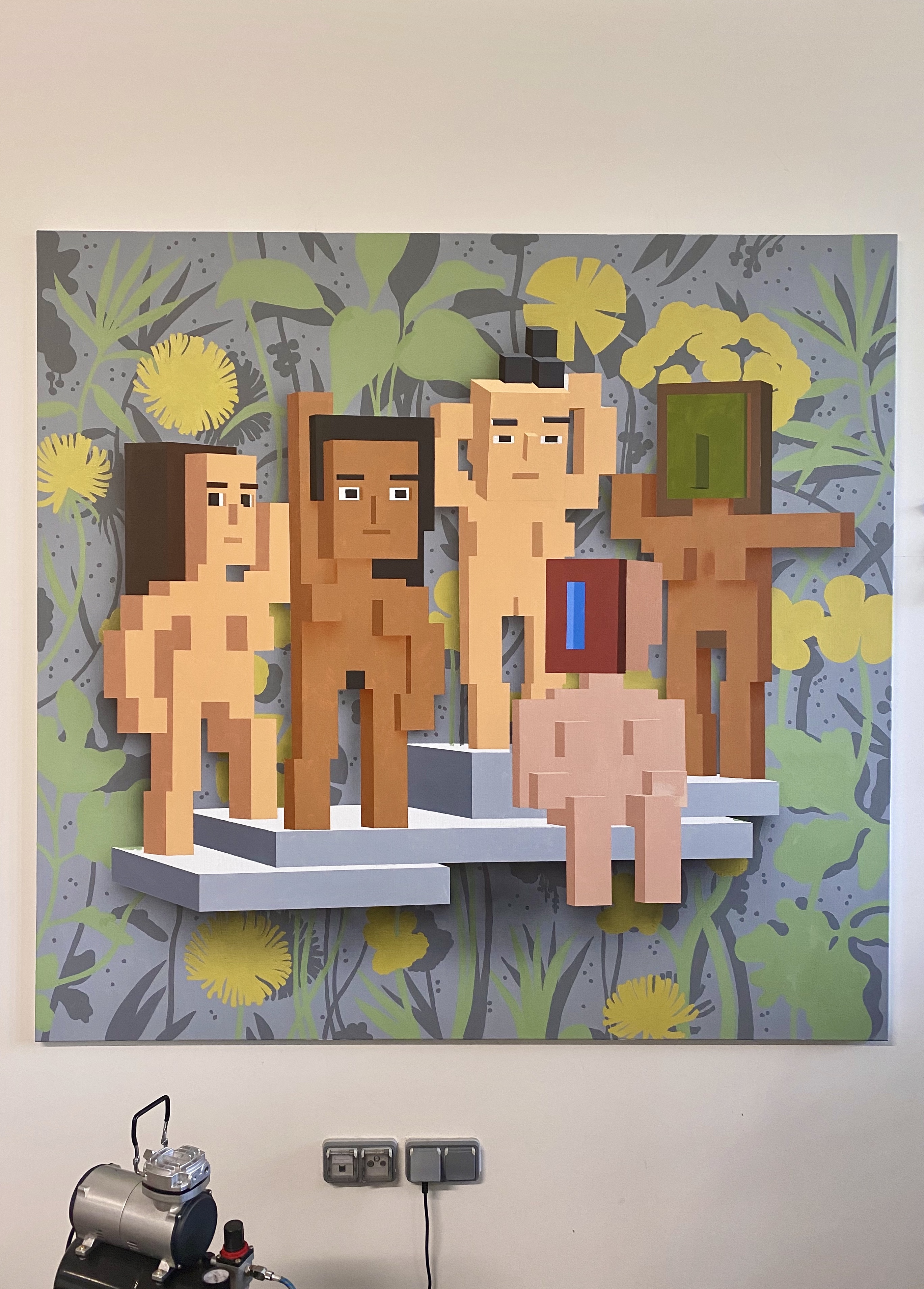

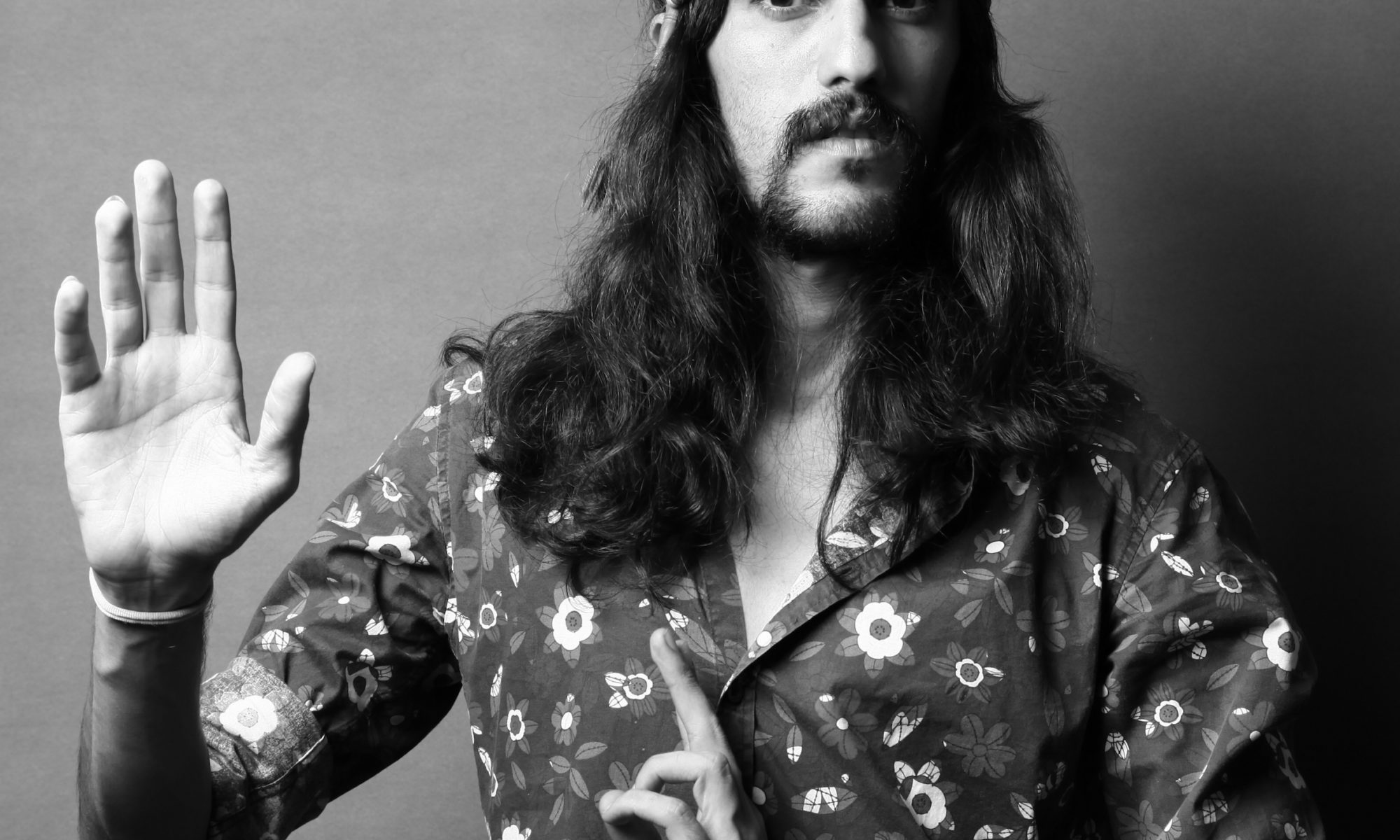

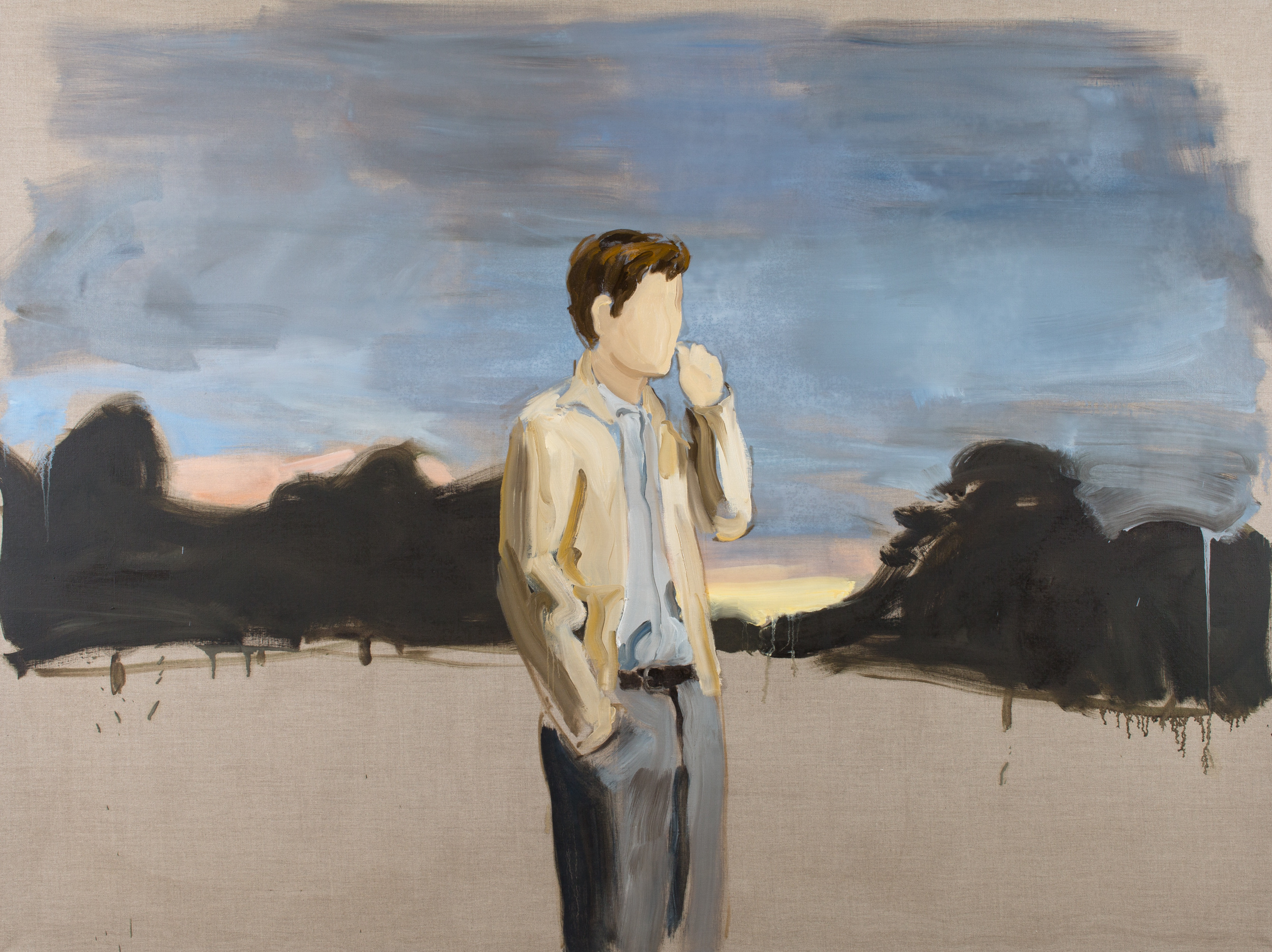

Everything here is art, Ready Made or her own creation, from the fridge to the armchair in the living room and the large panels of colored leather lying everywhere recovered with graffitis in fluorescent colours. I’m struck by this creative energy, it’s fresh, dynamic, experimental, spontaneous, almost quite punk. I can see these young people, in their coolest hipster outfits, art lovers, designers, curators, all around this apartment discussing intensely, and there is Mimi, the artist with these sparkling eyes and smile, standing in front of her artwork and swaying to the music. For one moment I forget that I’m in Tehran until my gaze falls on Khomeini’s portray outside the window on the house wall just opposite of Mimi’s studio. I pinch myself. I realize that I’m in the capital of the Islamic Republic of Iran…

It’s January and I’m in Tehran to participate at Teer Art Week, organized by Hormoz Hematian, founder of the influential Dastan gallery, and by Maryam Majd of Assar Art Gallery. Dedicated to contemporary Iranian art this event takes place at the same time as the Tehran Auction that breaks all the records in the last years in Iran even though the country’s economy is squeezed by the US sanctions.

Teer Art Week is an extraordinary and unique art experience among international art events: It’s a great invitation to discover galleries in Tehran and meet Iranian artists at their studio.

It focuses on this unknown art scene that I’d like to bring to light.

Since the Trump administration hit Iran with sanctions in May 2018, the Iranian currency has lost 60% of its value, and inflation reaches almost 35%. The country is economically and politically isolated, all the exchange offices are closed. However in this difficult context art becomes and investment of the rich of this country. But mainly established artist benefit from this evolution, most of them are even already dead.

Young artists, for their part, are rather victims of this political and economical situation: Extremely increasing prices concern also their work tools such as paint, canvas, painting brushes, paper, film rolls and the development of photos, etc. that are mainly imported from abroad. In addition to that rising housing prices force them to live at their parents’ house or leave the city.

“The Iranian art scenes, from the most confidential artist to the more mainstream, is extremely interesting and exciting and breaks all the rules and boundaries.”

Jean Marc Decrop

Expert in contemporary Chinese art and collector of contemporary Iranian art

“The contemporary art scene in Iran has extremely evolved in the past years. It’s very creative and has definitely an international level and credibility.

However, the artists are confronted with limits that they need to subvert every day. It’ll be important to reinforce the international relations in order to gain recognition and conquer new markets outside the country.

That’s the goal of Teer Art Week and the German Embassy likes to support this project.”

Justus M. Kemper

Head of Cultural Section at the German Embassy in Tehran

“I believe that one day Iran will be the center of Art in the Middle East, but currently the contemporary art scene here is like the rest of Iran, a mixture of many narratives. Even though a few galleries are attempting to give more attention to contemporary art, happenings and events still concentrate mostly on modern art.

Fortunately there are many contemporary artists and there is a huge potential for growth in this area.

Teer Art can be very helpful, especially in educating art patrons and push collectors more towards contemporary art.”

Maryam « Mimi » Amini

Contemporary female artist who lives and works in Tehran

“As the number of galleries has increased a lot in the last years, the art scene in Iran has become more mature, more divers, with more interest from top international collectors as well as top institutions. This confirms that the contemporary art scene in Iran will be the next scene to keep an eye on.”

Arian Etebarian

Founder of the platform of Iranian art www.darz.ir

Credits:

Photos by Anahita Vessier and Roxana Fazeli

Text: Anahita Vessier and Nada Rihani Teissier du Cros

Translation: Anahita Vessier

https://teerart.com

Share this post