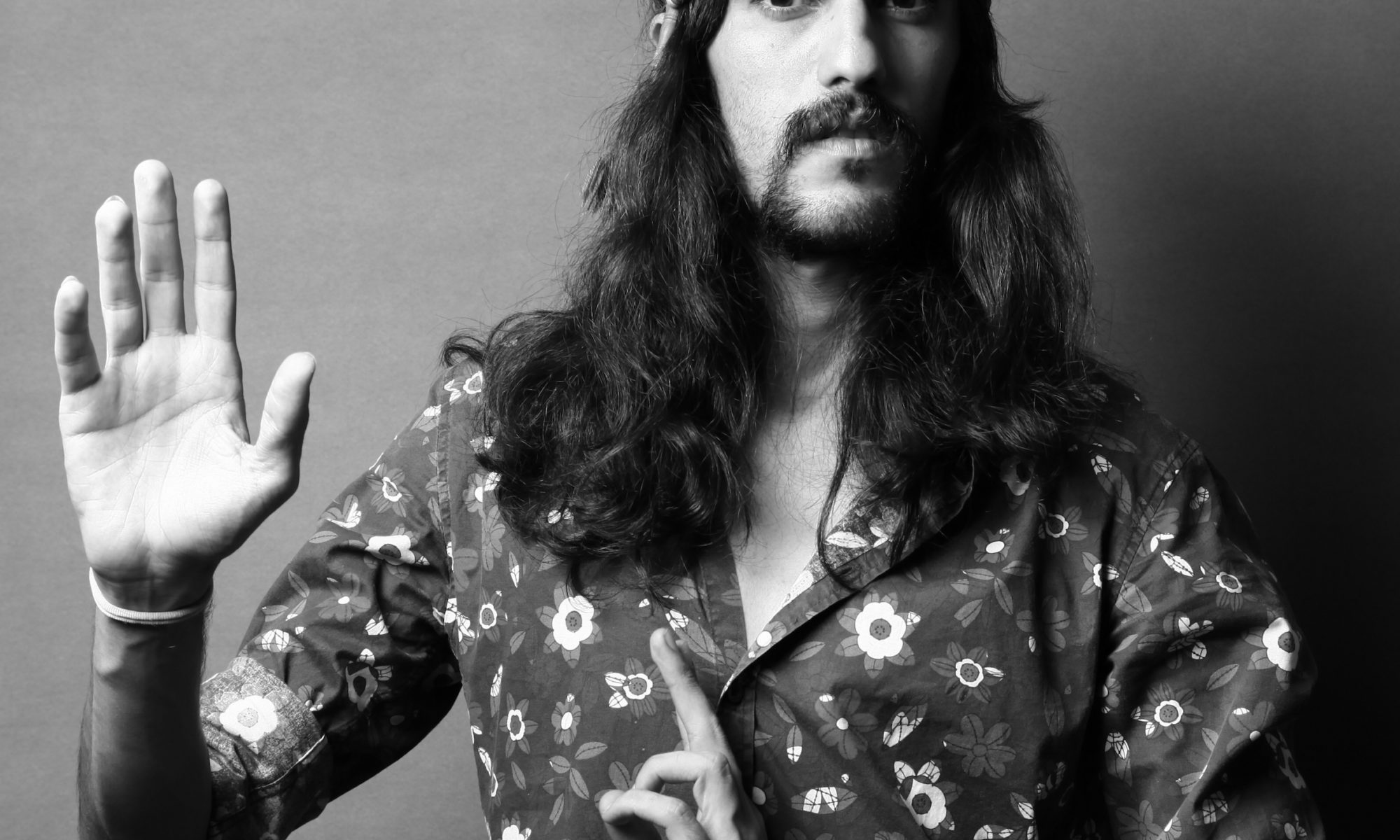

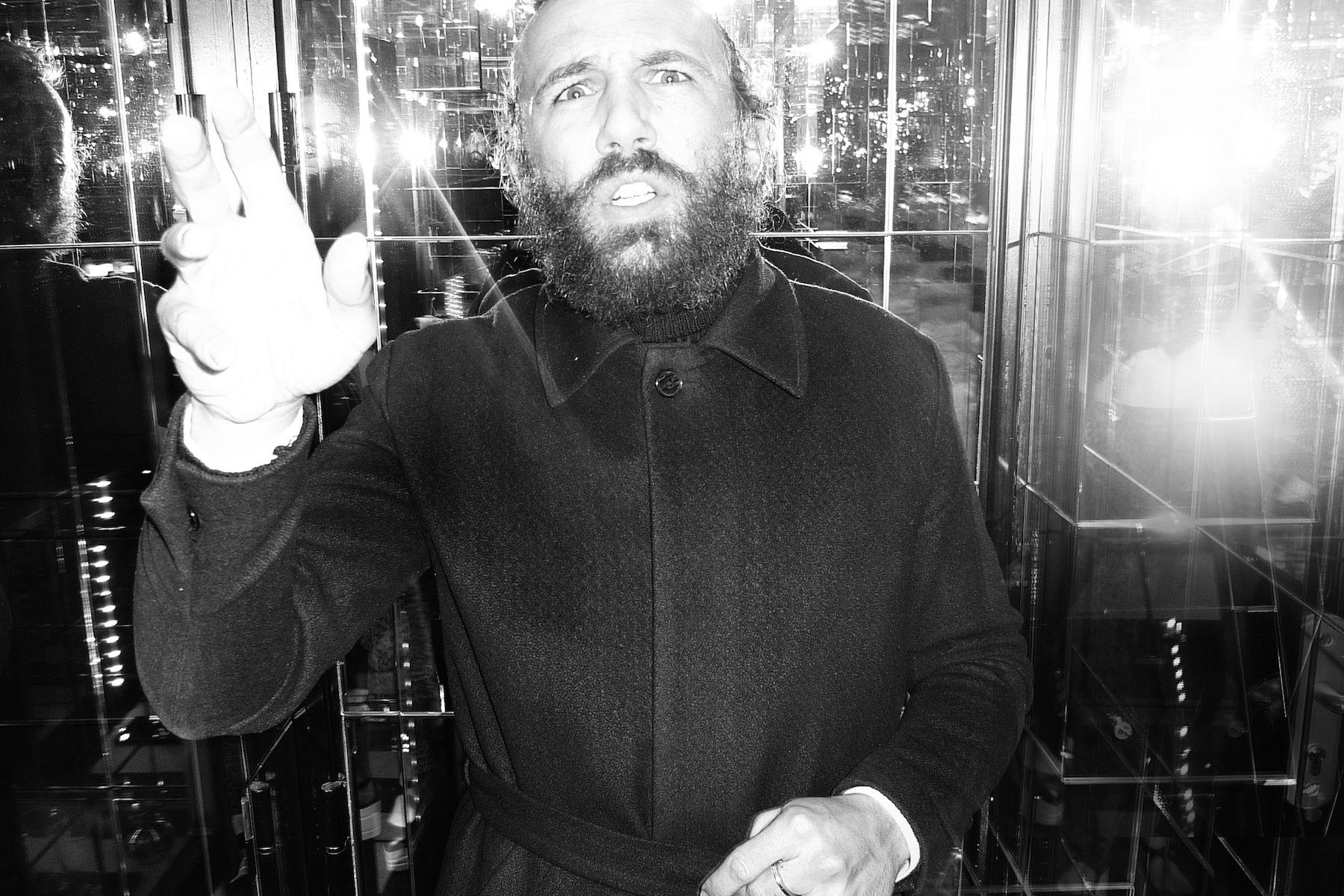

GIDEON RUBIN, Craftsman of faceless memories

Gideon Rubin is a contemporary Israeli artist and a rising star in the international art scene.

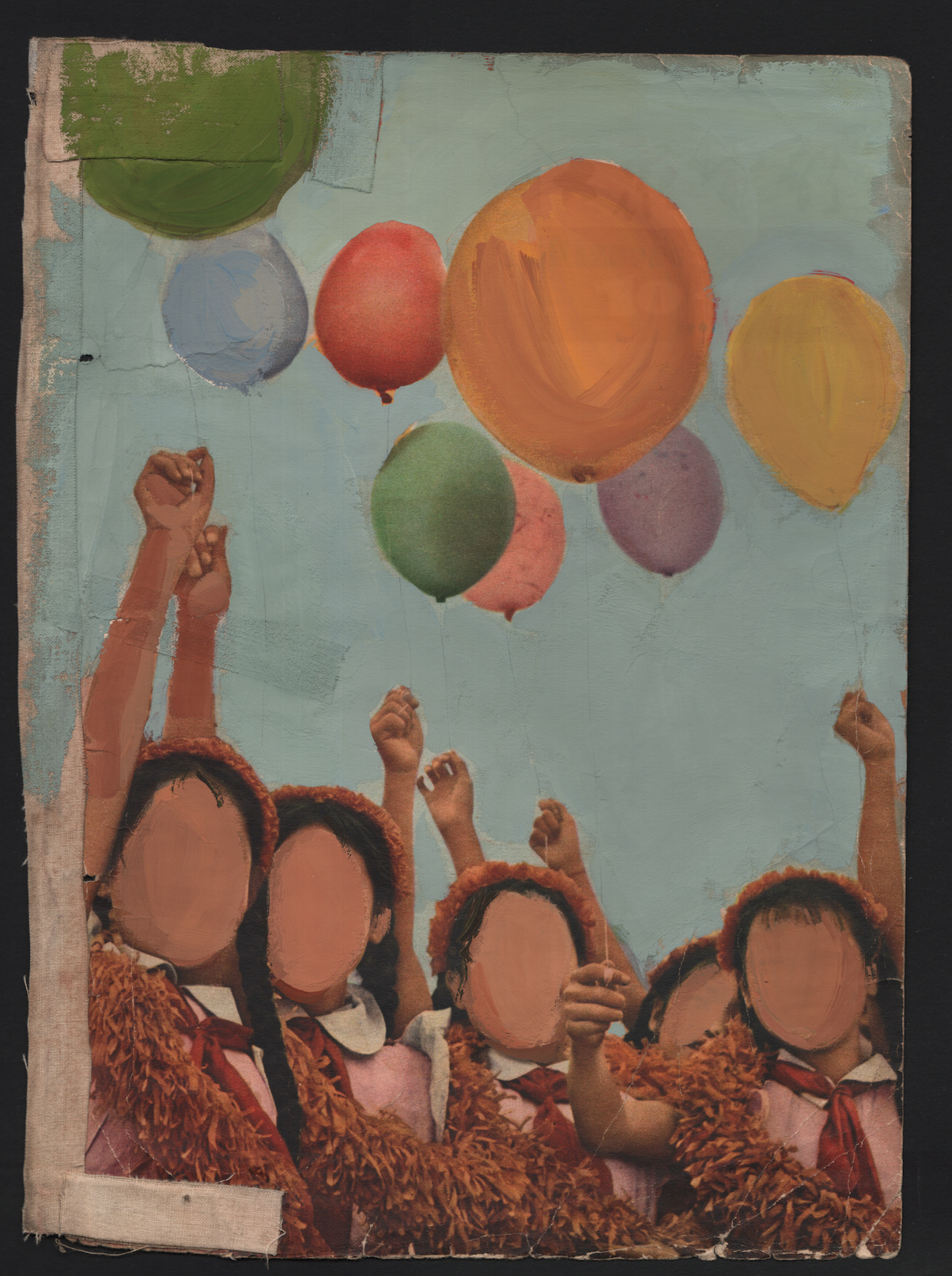

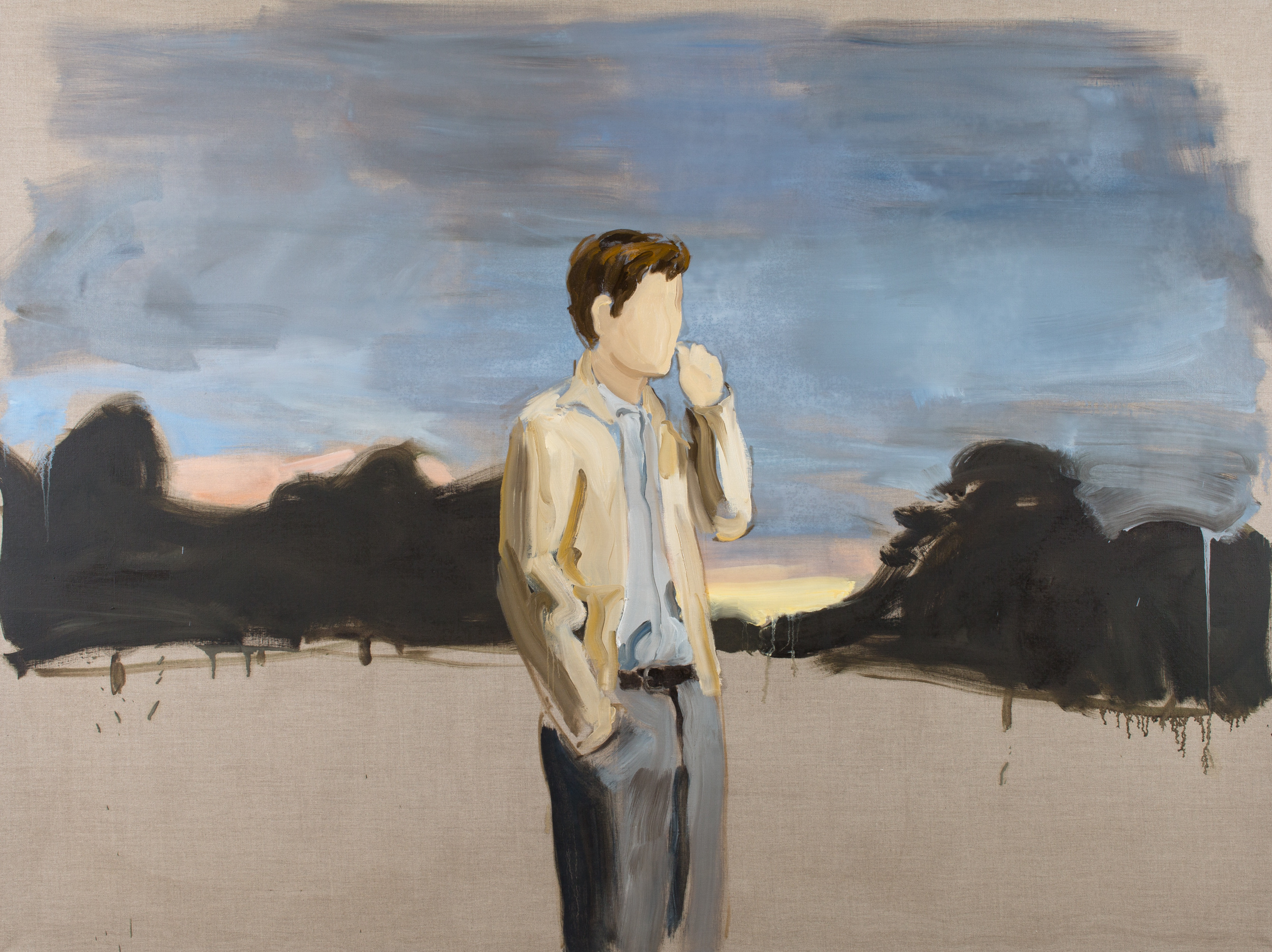

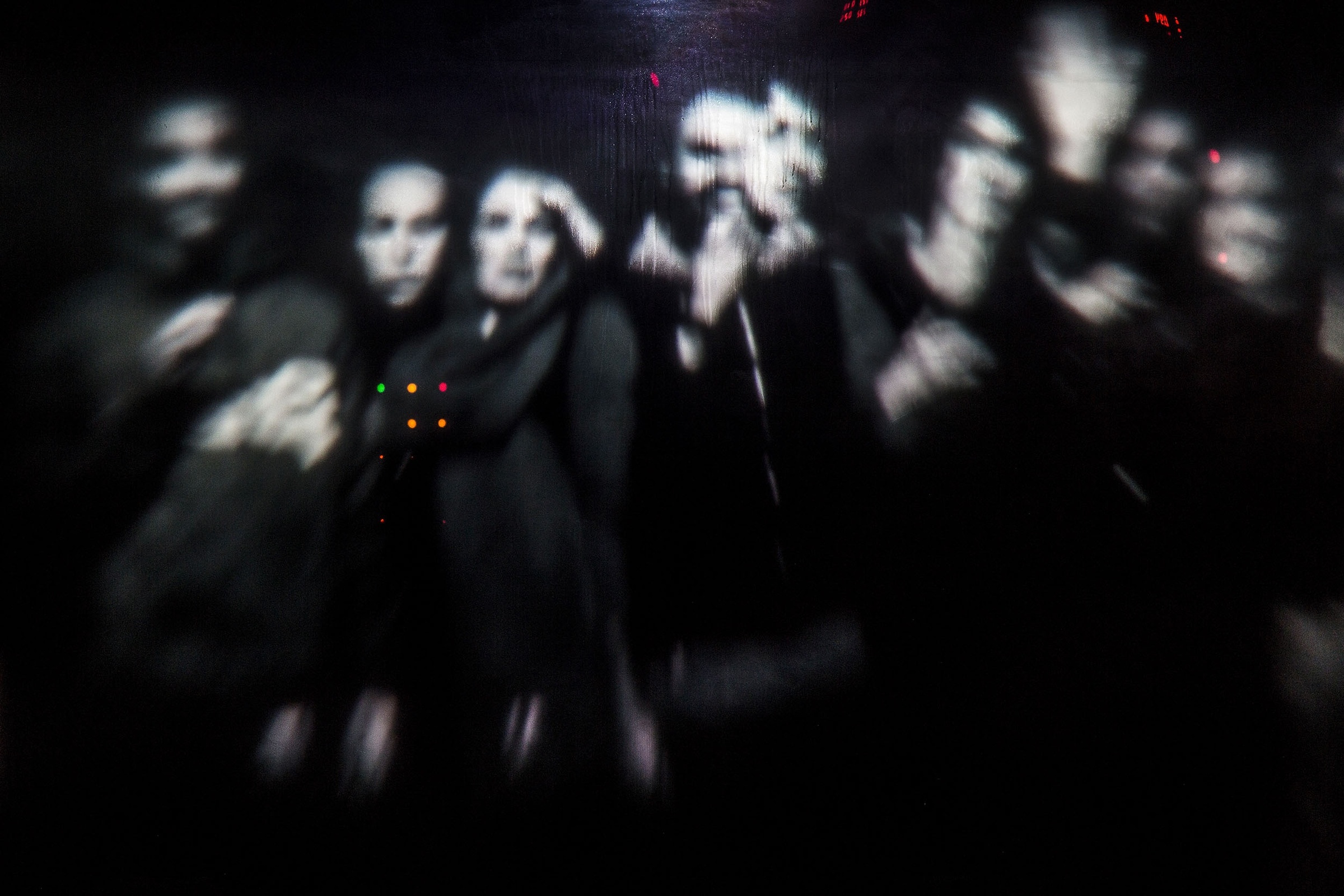

His work is about the memory of something that is at the point of fading away. By blurring identifying details, erasing the facial features of human beings, he invites the viewer to complete these unexisting details by using his very own memories. This “dialogue” creates a very personal relationship between the artwork and the audience and evokes a feeling of intimacy and nostalgia.

Being the grandson of Reuven Rubin, the famous Israeli painter, did this influence your decision to become a painter?

Looking back obviously it did but it took a long time for it to come out.

I was about 22 years old when I started painting and if you’d ask me before what’s the least possible career or job prospect, painter would have probably topped the list, mainly because of my grandfather and the position he occupies within the canon of Israeli art. For years, for me, viewing his work was actually tainted by the fame his work carries with it back home.

“It was not just a flower, a house or a portrait, it was a “Rubin” first.”

I guess this was probably the main reason that when I finally did find ‘painting’, a life long commitment, I chose to do it outside my home. It was only then that I discovered so much of his work; sensitivities, paint application, tonality and how much of it actually filtered to my DNA.

You were in New York on September 11th, 2001. Did this experience have an influence on your work?

It changed my life so it definitely changed my work as well.

Before 9/11 I used to paint from observation, focusing on full figure self-portraits that took months to finish.

When I got back to London on the first commercial flight to leave NY, it felt as if I escaped hell. I was so happy to land in London, I wanted to kiss the ground but I just couldn’t paint like before. I couldn’t look at myself in the mirror anymore so I began making these small toy still-life paintings.

Instead of one portrait, painted for three months, I painted now three paintings a day. It felt as if I was unloading a huge burden. As artists we are lucky, we have our work in order to deal with all the shit that happens around us.

Being a sort of « craftsman of memories », each of your paintings has this incomplete detail of faceless human beings. What is the reason, the intention behind these portraits without features?

More than anything it’s an abstraction tool, a way I enjoy directing and dissecting what I see and the surface of the painting. Simplifying it.

Growing up I was fascinated by the little figures in my grandfather’s landscape paintings; just little blobs of paint to describe a face, limbs or body. In my work I try to strike a balance between the general and the specific, the ‘public’ and the ‘individual’, which I find fascinating.

When I began erasing the facial features it was something altogether different. Painting old toys I was reacting to the physical erasure of the doll features after years of being handled and played with kids. As my work shifted back to portraiture, I found out fairly quickly that I can describe what I need without the features.

“I was and still am fascinated by how much information we gather between us that is outside the face.”

Our mannerism, style, the way we dress, walk etc. We ‘read’ each other and any human portrait, by first and for-most our facial features and then everything else. I’m interested in reversing this process, everything else comes first and then leave an opening, a question mark. an untold story. For me the act of erasing is as important and positive as a mark making.

While working on your paintings, how do you perceive time in these very intense and creative moments?

It’s difficult to put these moments in words, especially, if words are not your thing and you don’t want to sound cheesy.

But if I have to I can say that I learned not to look for these moments. Just work and work. When they come, it’s great, you are in the action itself and there is nothing else, but as soon as you begin to think about it, acknowledging you are or were in “it”, it is gone.

Is there an author, an artist, a musician that has changed your perception of art and inspired you in your process of creating?

Velasquez, Goya, Rembrandt, Chardin, Soutine, Guston, Manet, Bacon, Freud, Morandi, Alys, Richter, Rotheko, Matisse, Picasso, Diebenkorn, Hemingway, Kerouac, Camus, David Grossman, Primo Levy, Leonard Cohen, Bowie, Dylan, Allen, Tarantino, Almodovar, Nina Simone I can go on and on…

What do you feel when you’ve just finished a painting and you look at it?

Disappointment, as if I could have done it better. Sometimes it’s true, luckily sometimes not.

Is there a quote, a proverb that guides you through life?

“Inspiration exists, but it has to find you working.” (Pablo Picasso)

“An intellectual says a simple thing in a complex way. An artist says a complex thing in a simple way.” (Charles Bukowski)

Do you work with music? What’s your favourite musician that you listen to at the moment in your studio?

It shifts, at the moment I’m listening to a bit of soul like Erica Badu, Lauren Hill and my usual outdated Jazz, Nina Simone, Coltrane, Miles Davis to a bit of Bowie and Leonard Cohen. Lately, I find I listen more to classical music. Piano, a lot of piano…

You were recently invited by the Museum of Contemporary Art of Chengdu in China to a group exhibition under the title “Memory Goes As Far As This Morning”. This invitation also gave you the opportunity to visit the province of Xinjiang which is home of the Uyghur, an ethnic minority that primarily practices Islam. How was this experience for you?

It was really quite remarkable, a once in the life time experience. I was specifically interested, as my wife, although mainland Chinese, was born in Xinjiang, in Korla and I have heard much about the Turkic peoples where she was born. Their look is closer to Israeli than Chinese she used to tell me and that I would like the food.

“She was right in many aspects and I could find quite a few similarities between the Uyghur people and people from the Middle East.”

It was a very different experience than traveling in China, mainly due to very tight security, a result of years of political unrest, which I have to say added to an uneasy feeling throughout but this huge area has so much more to offer, a unique history of the ancient silk road which is incredibly preserved due to the dry weather conditions, to the highest snow peaked mountains that look as if they were taken from the Swiss alps.

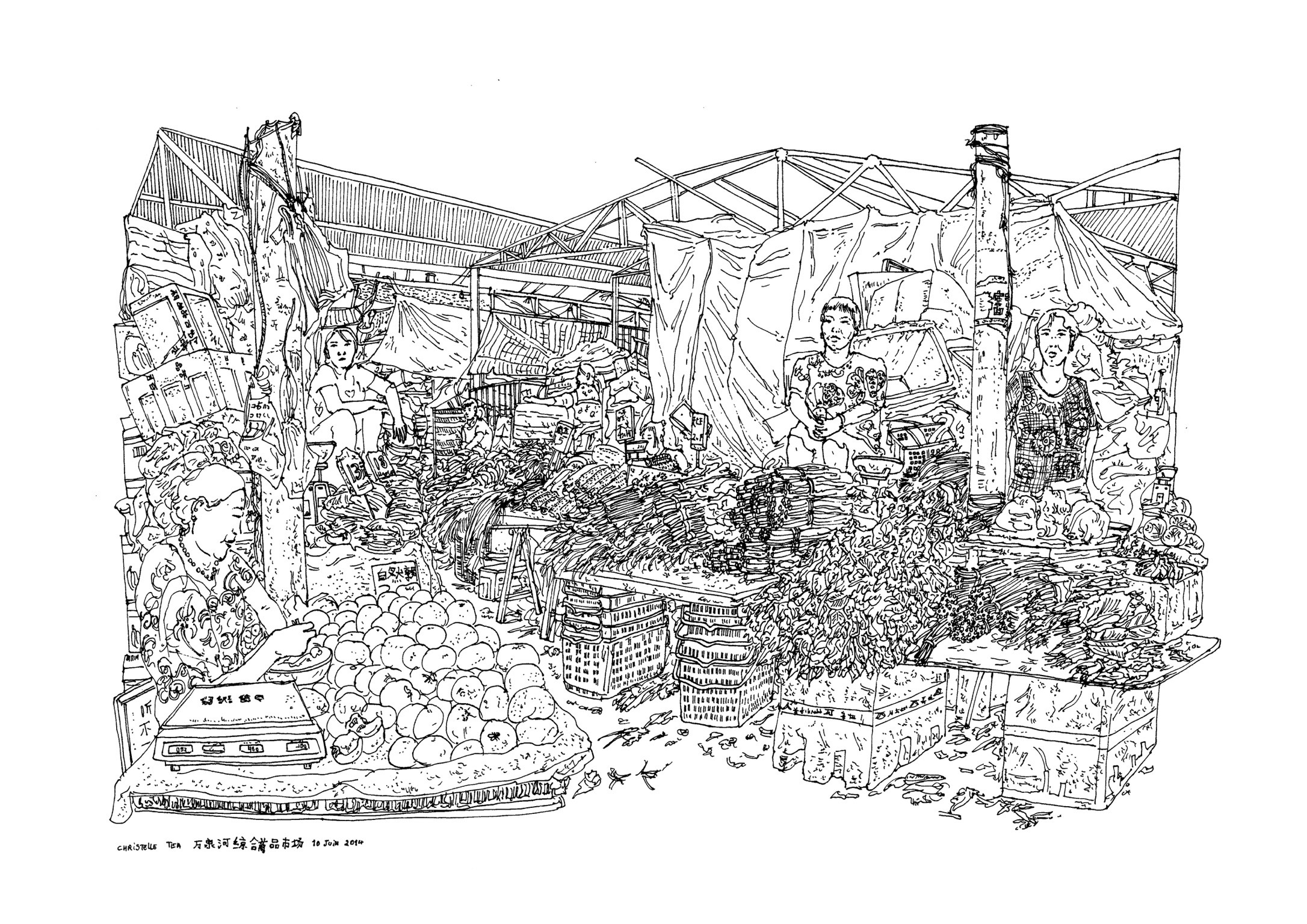

From the vibrant markets full of spices to the beautifully hand crafted artifacts, and the beautiful scarfed women, it all seemed to belong to a different time and a magical place.

What comes to your mind when you think of Iran?

Generally I always think of how I enjoy meeting Iranians since I moved to NY and then London. I find so much in common and much to appreciate, from my point

of view, food and cinema come first to mind. ‘A Separation’, ‘About Elly’…

I also think it’s a shame that I can’t visit.

I see the meeting points, the dialogue, the art.